David Stairs

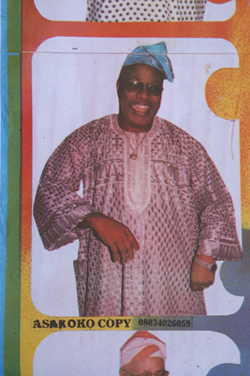

Our son thinks he’s a Ugandan. Perhaps spending three of his first eight years in Africa has had something to do with this. Or possibly it’s because he attends Ugandan primary school, where he’s had to learn the appropriate accent, gestures, and facial expressions in order to survive. Whatever the case, he has adjusted well to his adopted country and culture. When he was younger we took Luco to be fitted for a kitenge, or African dress ensemble. He had his portrait taken in it in 2003, and thereafter whenever he dressed up he wanted to put on his kitenge. Over the years Luco grew from a pre-school child to a primary student and, along the way, his beloved kitenge became too small. On this visit to Africa, we told him he would be fitted for a new one. This made him very happy.

At the yardgoods stalls, Owino

One recent Saturday Sydnee took Luco to shop for fabric. Adjacent to the Owino Market in downtown Kampala there are hundreds of stalls selling yardgoods. Six meters is the length for a traditional women’s dress, but for this job three meters would do. Luco had an idea of what he wanted, something African tie-dyed, like his original kitenge. After five or six stalls he found what he was looking for and purchased three meters for 10,000 shillings (about $6).

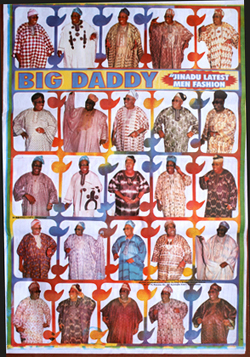

The next step in the process was choosing a motif. The seamstress Sydnee had contracted brought several pattern posters from which to choose a garment and embroidery style. These posters are designed and printed in Nigeria using traditional cut and paste layout techniques. Many different garments are modeled by the same person, photographed, quickly cut out and pasted up, then hand separated and printed on cheap A1 poster-size paper with all the glorious mis-registration such an approach is liable to.

After Luco chose the style he liked best, the seamstress measured him and went away with the fabric. She does her work rule-of-thumb, which is to say she works directly on the fabric from measurements without a pattern. After the garment was cut, she took it to an embroiderer. Most embroidery is done by men. The work on Luco’s kitenge is asymmetric, and shows traces of three distinct but similar main thread colors well chosen to complement the green/blues of the fabric. Although the workers use programmable machines, the many curves are sewn at high speed and must be guided by eye. It’s quite elegant and demanding work. A good embroiderer can make 25 pieces in a day, the equivalent of about $20 income.

Embroiderer at work

After the embroidery is complete, the garment is returned to the seamstress for final assembly. The skill of the seamstress can be seen in the way she relates the fabric’s colors and patterns to the garment’s style. About ten days later she returned for final fitting. After adjusting the drawstring pantaloons, Luco was invited to try the ensemble on. He was visibly excited; he liked it very much.

Kitenges are not the everyday dress of Ugandan men, who are more inclined toward collared shirts and seamed slacks. It’s surprising the first time one sees a man apparently wearing pajamas about in broad daylight. But I have to admit, these originally West African garments in bright colors with fantastic embroidery are much more striking than the average suit and tie, and cooler, too. Their design process is reminiscent of a time in our nation’s past before ready-to-wear took over the retail clothing trade. For $22 Luco will be the best-dressed kid in his third-grade classroom, at least until the next size change.

David Stairs is founding editor of Design-Altruism-Project

March 26, 2007 at 2:32 am

That looks great, Luco! I’d love to see what the embroidery looks like in real life!

See you soon! Fred

March 19, 2007 at 11:40 am

Hey Luco; that looks awesome!! We have a kind of shirt here in South Africa that looks similar. Mr Mandela was famous for wearing them. He was our previous President. Not too many people wear them. Usually if we see someone wearing something like your Kitenge around Pretoria where I live, we know that they’re from Uganda or maybe Nigeria. Anyway; I’m glad to see your new Kitenge worked out so cool. Enjoy wearing it and say hi to your dad and mom for me. From Tasos