David Stairs

For most of my adult life I’ve been obsessing about homeostasis, the scientific concept for stable state equilibrium of systems and organisms, currently popularized by the term sustainability. My first two published design essays 1997 & 1999 were about the conflicted state of design criticism in the clash between biophilia and what I then termed “technophilia.” It seemed to me at that time that there was really not a choice between the two. While we tend to think technology is ascendant, biology is true destiny and will prove out in the end. Whether or not it will be an end that benefits humans is the great unknown.

More recently, I’ve marveled as the activity related to sustainability, so long overlooked, has reached fever pitch in some circles. The events in Copenhagen during early December and in online campaigns in support of an accord there have been intense. Yet, on a recent episode of Charlie Rose, economist Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia’s Earth Institute stated that we have failed utterly in our treaty obligations under the 1992 Global Climate Treaty, ratified by Congress in 1994. So, if the U.S government can’t deliver on its treaty commitments, and the UN organizers in Copenhagen are now admitting that maybe they aimed a bit too high, what’s to stop others from trying?

Sustainable initiatives among designers, for example, have recently been approaching a level that can best be described as fashionably PC. In October 2009 I participated in The Designers Accord’s global “summit” on sustainable design education. Around 100 people adversely affected their carbon footprints to travel to San Francisco for two days of rigorously focused head banging in an effort to outline what a sustainable design curriculum might entail. Representatives of sustainability initiatives at Pratt, Forum for the Future, Worldstudio and elsewhere participated as both presenters and group mentors.

One of The Designers Accord summit’s sponsors, Sustainable Minds, actually produces life cycle analysis (LCA) software designed to “enable environmental life cycle assessment and rapid iteration of product concepts in the earliest stages of design.” Invoking “Okala”, a life cycle assessment method for evaluating environmental and health impacts of the products marketed in North America, Sustainable Minds is running workshops that “teach participants how to design whole systems from a life cycle perspective, and how to estimate, model and make design decisions based on environmental impact.”

Almost all of the plenary speakers at the summit were incredibly upbeat about design’s influence on the world. In fact, one of Worldstudio’s initiatives is entitled Design Ignites Change. It took waiting until the final speaker of the weekend to hear a balanced presentation. Philosopher Cameron Tonkinwise of the New School, like the boy observing the emperor’s nudity, deflated the collective euphoria when he pointed out that, if designers truly wanted to be sustainable, they were not doing nearly half enough; even our language is insufficient to the task.

The AIGA and its minions, never far from any source of current cultural hysteria, is very active in its efforts to colonize sustainability. Having recently created a Center for Sustainable Design (unfortunately, a CFSD already exists in the UK), AIGA has gone on to develop The Living Principles for Design. This document compiles “the collective wisdom found in decades of sustainability theories” and attempts to apply them to a “quadruple bottom-line framework for design” that includes culture along with economy, environment, and equity. Most AIGA activities, including their upcoming education summit, response_ability, and many of their regional chapters, are heavily promoting this initiative following its introduction at the national conference in Memphis in October.

Not to be outdone by the AIGA in this land rush to commercially annex sustainability, the good men and women at IDEO, perennial conference attendees and professional media darlings, have developed a blog entitled Living Climate Change, a site that invites participants to “imagine what life will be like in 20 to 30 years.” While this sustainability-leaning version of South Park style quickie animations may not exactly be the solution to our woes, it does invite playfulness and participatory speculation, and may even provide IDEO with some fresh ideas from outside the boardroom, although all the posts to date seem self-promotional.

Oh, and let’s not forget JWT’s initiative. Over there the green group is known as JunkWasteTrash, three things the agency has created plenty of in its history. Perhaps this knowledge has even added guilt to the company’s own anxiety index.

Lest you breathe the word “opportunist” when wondering aloud where all these “thought leaders” were twenty years ago, they’ll be at pains to remind you that, at that time, sustainability was an idea whose moment of critical mass had not yet arrived. Of course, it’s a truism of free market economics that, if the government stays out of things and markets are allowed to develop independently, then free enterprise will find necessary solutions. Last year’s near economic meltdown is an excellent indication of the wisdom of this philosophy, right?

If you’re not entirely comfortable following the assurances of either “the world’s leading design firm” or the blandishments of “the association for design” regarding sustainability, there may be hope for you yet. There isn’t one reference in The Living Principles to Herbert Simon, Rachel Carson, Victor Papanek, Aldo Leopold, or Barry Commoner and, outside McDonough and Braungart’s Hannover Principles, a lot less recognition of the concept of species interdependence than what James Cameron offers in Avatar. Most of the “collective sustainability wisdom of the last fifty years” dates post 1985, and the great majority favors design initiatives.

One of the best initiatives I’ve come across, John Thackara’s recent posts on his Doors blog (including a positive post-Copenhagen take), isn’t even mentioned in The Living Principles. Thackara, who was once a great believer in electronic networking and an avid conference attendee, has proved himself capable of reform. These days he eschews his former faith in the technosphere, and, like Candide, prefers to metaphorically “tend his garden” by reducing his globetrotting conference attendance.

As for IDEO’s donation to the literature, other than authoring a few tomes on human centered design and proselytizing the business community, it seems designers there, as elsewhere, are busily expanding the concept of sustainability beyond what it can, uh, well, sustain. Designers are bound to muddy the distinction between the scientific meme and the cultural one. Since design is increasingly a hybrid of the creative arts and the social sciences, designers are destined to have it both ways, often with confusion and conflict (not to mention “conflict of interest”) ensuing.

As we approach the fortieth anniversary of the first Earth Day, the brazen capitalization of our environmental crisis by those working in design circles seems less like the co-opting of a forty-year-old environmentalist philosophy by a business plan than an admission by the profession that it neither sees the future clearly, nor cares much about anything beyond its own economic survival. While profiteering from sustainability by any profession may seem a lame undertaking, substituting our immediate personal prosperity for Our Common Future, it is yet another instance of business-as-usual for what McLuhan called the “frogmen” of sales rhetoric masquerading as social entrepreneurs and science popularizers.

Furthermore, few if any of these people are qualified to make the determinations being called for of what we really need in the future. For this they turn to TED presentations by scientists like Janine Benyrus and Amory Lovins and fascinate over concepts like biomimicry and systems thinking, as if there’s something new about them. Should we think locally AND act locally, as Thackara seems to be suggesting? Do we need the Iliad more than microwave popcorn? For that matter, should there be a law against printing on paper altogether? Until such a statute is passed, is publishing The New Atlantis more culturally significant than publishing Superman comics? Is Slow Food different from or better than the more traditional organic or macrobiotic food? Is driving an all electric car more ethical than reducing personal freedoms? Until we bring world population under control do any options much matter?

The one thing I’m certain of in this life is that those who boast most loudly about their current high standards, numbers of awards, and level of innovation are probably not the ones we want standing guard along the watchtower. Who better you ask? Well, perhaps some of those pesky activists who, while designers were busy burning from one excess to the next, evolved from treehuggers to WTO demonstrators to carbon tax advocates. Or maybe some of those modest science-types who’ve spent whole careers trying to get the world’s attention focused on this issue.

Least that way, when the call comes up to the ramparts saying there’s a sixty-foot high sculpture by Jeff Koons (the Odyssean master of recycling cultural detritus for gold) standing outside the gates, perhaps the guards will have the good sense to examine it carefully before claiming it to be the next great culture meme and dragging it inside the gates to auction for cap and trade credit.

David Stairs is the editor of Design-Altruism-Project

April 27, 2010 at 12:00 am

Sorry if I’m posting again, I’m a design student that is trying to understand what has happened and what’s going on now in design social/develompment discourse.In my researches I encountered the ICSID Interdesign. I’ve seen that you were collaborating/working with them…What do you think about the workshop strategy of them? It’s just another ineffective and harmful “parachute design” (Donaldson) experience?

January 21, 2010 at 8:41 am

What a great article and contributing comments. As much as profiteering from sustainability boils the blood and spits in the face of its ideology, I don’t think sustainability is the first, or will be the last cultural movement, that benefits the spotlight vampires. Life has a way of working these things out.

What I think is important, is to concentrate on what is within each individuals power to make change. If these conferences are not creating lasting change or generating actionable ideas, then go elsewhere. Don’t let others decide for you on how these things should work. As idealistic as it sounds, each of us has the power to do something. Sometimes it is a lot of guesswork and instinct. I don’t think Greg Mortenson knew where his journey was going to take him, or how many people would be willing to help him get there.

As designers, educators, activists or whatever else you may be, each person possess a unique set of skills and experiences at any given time. This gives you an innate ability different from anyone else to make an impact in your individual way. Take advantage of what you have. If this fits within the scope of the design industry then so be it. If it takes you on a journey down a different path, then let it guide you. What is important is to do something, anything. We need as many people on the bandwagon as possible.

January 19, 2010 at 8:30 pm

The Revolution lives on. Maybe in a small way but it still growing:

http://www.colbertnation.com/the-colbert-report-videos/262000/january-18-2010/emily-pilloton

January 19, 2010 at 3:22 am

Marco—

I’ve been to one Interdesign, although they happen all the time. I found that there were quite a few designers who donated their vacation time to trying to help out. I can’t say how effective most are. The one about alternative means of transport in SA went on to become a project at CAPUT in Capetown, and the government expressed some interest.

I fear that many of these experiences are as you describe them: designers parachuting in for a couple weeks because they can’t or won’t do any more. I made a number of lasting friends from my experience, and there’s something to said for that. Whether it was all just an expensive vacation is arguable.

DS

January 18, 2010 at 5:32 pm

Sorry if I’m posting again, I’m a design student that is trying to understand what has happened and what’s going on now in design social/develompment discourse.In my researches I encountered the ICSID Interdesign. I’ve seen that you were collaborating/working with them…What do you think about the workshop strategy of them? It’s just another ineffective and harmful “parachute design” (Donaldson) experience?

January 15, 2010 at 6:05 pm

Hi david

I am dazzled by your lucidity and criticism, but it could be even better if your criticism become a bit more “constructive”. I think you have all the abilities to do it.

thanks

January 14, 2010 at 2:22 pm

I agree completely with the fact that something dramatic needs to change, but how is that going to be done? Any initiative is going to be scrutinized by a group that is negatively affected by it. It has been mentioned that a new economics metrics needs to be in place. That is a wonderful idea, but the economy is already run by the banks as we have all noticed over the past year. It has been said that we can start farmers markets and community programs. That is a great idea too, but what about the inner cities, underdeveloped areas, segregated communities, gangs, etc. Ideas like community programs are great, but they fail to truly reach where the most severe problems are.

We need to make sure that the initiatives that get the most attention are focused on the fundamental issues of water, health, family values and community. We need to speak to the companies in business terms and the people in people terms. We all want the same thing, we just need to know how to ask.

January 11, 2010 at 4:08 am

I too attended the Designer’s Accord Conference in San Francisco. After the first day I walked back to my hotel frustrated because we weren’t able to penetrate below surface issues in our discussions.

Designers must think deeply about our culture and forge a new way of living. Capitalism as we know it is fundamentally at odds with the goal of living sustainably. You mention John Thackara’s blog. His call for new economic metrics gets to the heart of the matter. He says that “to understand what could replace the ecocidal economy we have now, we need to focus on a different kind of culture-culture as a description of the ways people live-and can live differently”.

All other design issues pale in comparison.

January 9, 2010 at 4:22 am

As Cameron Tonkinwise, of the New School talked about in San Francisco; even the most sustainably designed buildings will not be sustainable by themselves. Everything depends on the people inside. They need to care. Designers, Corporations, governments, community programs are all great approaches to the enabling the continuing of our species existence on this world, but the majority is still ruled by the individual.

I would like to see designers make sure all of their efforts are working towards the same goal. We all need to aim our efforts at the base of the proverbial fire. By “we,” I mean every entity and super-organism on this planet. The only way the complex problem of attaining global sustainability will be solved is by drafting a comprehensive “deign brief.” Any individual, group or committee would find it difficult to solve a problem if they did not focus on the fundamental causes. They may make progress and their intentions may be driven with the utmost sincerity, but they critics will always find the jujitsu leverage point. We would be best served by finding the Jujitsu Leverage point of the problem we would like to solve as Illustrated in the book Massive Change; a book published as a result of the efforts at the Institute Without Boundaries.

The cause of the current problem is people. We could educate them! We need to apply the design process to design education to make quantitative proof that the design process can make design education even more proficient in the development of critical thinking and global awareness of the future leaders. Once that is accomplished, the unbiased and objective design process can begin to be welcomed into political circles. That could eventually lead to a truly bi-partisan approach to education reform in America and the world.

January 8, 2010 at 5:19 pm

David

May I join you with pointing out these contradictions of the designerazzi? 🙂

Eric

January 8, 2010 at 5:08 pm

Eric—

I’m certainly NOT opposed to sustainability, as stated in my opening remarks. I’m desperately interested in preserving the natural environment. I also realize that I’ll have to suffer the opportunists among what you call the “designerazzi” for the foreseeable future. I reserve the right to point our their contradictions.

David

January 8, 2010 at 1:32 am

David

I’m behind your words in the article, however as “trendy” as sustainability has become, it is still truly the only way our civilization will continue in the future. There must be a balance between what we take away and what is put back. We must have clean air, land and water, and plenty of all – as populations still grow. I think what is extremely damaging to becoming sustainable is our own egos. The current game dictates that we must be the champion of a movement and capitalize on that fame (which I believe is how you might view Valerie and IDEO). However “being sustainable” does not fit in our usual game. It is a completely different way of looking at the economy, our lifestyles and what we create. So I also argue the “hero” game which is very prevalent in the “designerazzi” community must go away. It is all very utopian for sure, and possible a bit naive but incredibly necessary. All of us are affected, including designers, so we must all be part of the solution. If the problem is solved, we are all the heroes, all the billions that took part, not just the guy in front of the parade.

Thanks for a great piece, my students will be reading it.

Eric

January 7, 2010 at 9:52 pm

Hi david,

23, just graduated Product Designer. One of these who are trying to learn something. I’m really interested in having a balanced life between tech and nature and lately these last years i have seen this sustainable-design “boom” and honestly it starts to piss me off, the fashionable part of it. So thank you so much for this divergence discourse and tips (names, links).

best luck

January 7, 2010 at 9:13 am

David,

Thanks for this excellent and thoughtful [as always] piece. It’s true, of course, that too many design for sustainability actions lack modesty. Designers have been major beneficiaries of the consumption-creating industries that created the mess we’re all now in – and we need to fess up to this before stepping forward to fix the world. But in mitigation for their eco-narcissism, bear in mind that designers face a *big* ask: to stop the vast majority of the stuff- and communication-designing that they have always done. Besides, nearly all the designers I know are as virtuous as Neytiri compared to the greenwashing types one encounters in other industries.

January 7, 2010 at 5:50 am

It saddens me to think that the idea of living a sustainable lifestyle is the “fashionable” thing to do. At what point did jumping on the let’s-all-join-hands bandwagon become the diluted, comical meme that it is today? Granted, the movement towards a more altruistic, manageable society is not a new idea. Practically every group (including designers/”creatives”) has had their hand in sustainable living in recent memory. At one point, the design community lost their way. This meme isn’t quite LOLCats or that Star-Wars kid, but it leaves me with a bitter taste, nonetheless.

Instead of taking a truly active, revolutionary role in improving our world/selves, there is a general air of milling-around and self-aggrandizement (Valerie Casey, I’m looking at you). Congratulations on participating in yet another photogenic summit, but what exactly did you accomplish? What tangibles resulted from this meeting of the minds? Have we gained any additional understanding of what should be done?

I remember a snippet from Victor Papanek that reminds me of design’s relevancy: “The only important thing about design is how it relates to people.” In lieu of asserting design’s importance for “saving the world,” all interested parties need to band together to make a positive difference. The objective would be to incorporate design theory into a variety of improvement campaigns, along with contributions from many other disciplines.

Now that many are aware of the need for change, I want to know what we have to do next. Give us guidelines or ideas for enhancing our environmental relations (Not all of us can be leaders, but everyone can pitch in). As mentioned in comments above, perhaps we should look at poorer countries and lead by their environmental example. Such cultures leave no toxic waste or lasting harmful material in their wake. Our somewhat wasteful lifestyle has not improved our environment, so makes sense to approach sustainability with an open mind and look to our neighbors for inspiration.

January 6, 2010 at 7:07 am

At the risk of sounding shrill, I would like to reiterate my plea to the privileged to critique their own excessive, disharmonious and unintegrated lifestyles built on delusions of endless abundance and absolute non-accountability, and urgently validate (and emulate) the more truly sustainable – though humbler and simpler (in material/luxury terms) – lifestyles of millions of poorer but no less happy ‘under-privileged’ who have lived their way for generations without seeking to disrupt or dominate anyone else, but who are today being disrupted and dominated by the relentless economic-political-cultural logic of infinite growth, abundance and non-accountability.

January 5, 2010 at 11:29 pm

I take it back. The improper allocation of resources is precisely the problem, seeing as how most foreign aid is squandered through cooperation with air-headed displays of the masculine. Many aid organizations are starting to realize that development resources (design ideas, agricultural support, whathaveyou) are only used properly if handed to women of the locality. If your design philosophy does not interact with women and children exclusively in deals concerning ‘the underprivileged’, then it is merely serving to empower those who drive shiny Pajeros.

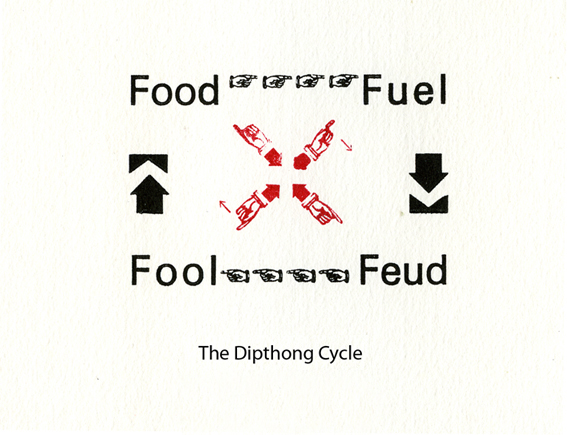

Your dipthong cycle looks like the Bermuda Triangle game board.

January 5, 2010 at 1:41 pm

Another timely, succinct, and wholly un-cynical post about the current altruistic raging in the design field. What’s happening in “sustainability” is similar to the the “colonization” threatening design education. There, we have consultancies like “NextD” loudly insinuating themselves into the discussion via force of relentless self-promotion. Or there’s celebrity design figures anointing themselves education experts because they’ve collated articles and class projects. (IDEO is aggressively setting up shop here also. Not long ago, I was alerted to IDEO’s innovative ideas about elementary education. They had, essentially, discovered the Montessori method—though they touted it as their development.)

The inability to recognize that there should be limits to self-promotion is a major problem in the field. I wonder if we can point to M&Co.’s famous “charitable” annual gifts as a turning point where good cause and good press was muddied irrevocably. There’s been a loss of recognition that the lack of self-effacement cheapens design and the cause. But it keeps your name out there….

Because people are fair-minded, especially towards those designers promoting “good” causes, few are willing to articulate the problem and call out the self-promoters. David merits praise for doing so fairly, clearly, and accurately.

January 5, 2010 at 3:59 am

Well, what did you expect? Sustainability is the new big thing, and every business is trying to extract as much growth, prestige and profit from it as they can – including design businesses. The fact remains that despite everyone agreeing on the crisis, no one questions the unlimited economic growth model, and that’s in part because the fast-growers and growth-engines of the moment (“BASIC”) see an opportunity to attain some sort of imaginary parity with the developed countries in the next few decades. Comparison, they say, is the biggest impediment to happiness/contentment – and as long as glaring inequality persists, the deprived will demand their right to parity with the privilged. The only way I can think is for the priviliged to voluntarily abdicate privilege and embrace simplicity – parity with the underpriviliged. Mahatma Gandhi gave up wearing British-style clothes and embraced the clothing and lifestyle of the poor – not just as identification but to enhance their dignity.

January 4, 2010 at 3:13 am

David,

Great to hear from you, Happy New Year! Your voice shines loud and clear in this great essay above. Thank you for sharing your passion and critique in hopes of further evolving our efforts of a healthy future. These are exciting times, with much at stake. The challenge as we’ve seen, and I think you are leaning on this, is that our designed products which reach the international community are those of great concern. I just returned home from a trip to Guatemala, and the amount of rubbish and waste was overwhelming. Lots of work to do…

Again thanks for these words. I look forward to being in touch soon!

Cheers,

Evan

January 4, 2010 at 2:38 am

With or without fond cultural standing, Jeff Koons will ever have enough blueprints and available kin to automate the production of uselessness. I medicate myself of this fact by consistently imagining all members of his cult making decisions from Ikea chairs elevated three feet above the ground. Of course the grand folly of designers cut from the mold of creative obsession is not an improper allocation of resources but rather the failure to realize that, as an event or act, design has not proven the least bit self-sacrificing when compared to the intentions of its promoters. ‘Designing’ from a distance (with respect to an area, an idea or a social insecurity) is as ethereal and unabashed as the cloud computation, that is, it exists in its own room with its own proprietary law. Such law may occasionally seek to engage truthfully through interface but is most often directed by compulsions of standardized self-preservation. At present, to talk negatively of this supervised cultural prod and poke is to be called out as the turd on the platter.

January 2, 2010 at 11:32 pm

There is not one simple solution to this complex problem that this post mentioned, as we are all aware. However, applying the same objective design process to the situation would work perfectly. Follow me here. While integrating sustainability into design education, we need to concurrently integrate design into education; public education.

If we want to sustain human life while maintaining an ideal state of freewill, all members of society to make educated decisions. Meeting a couple of times a year will not provide the radical innovation that is needed to save humanity from a collapse of the World community’s infrastructure, but only perpetuate the reluctant incrementalism that is rampant in virtually all entities in the world. We cannot compromise the intent of the sustainable meme. We need to be direct and stay direct, but as we all know, we need to provide a solution before we begin to complain. Entities have a tendency to deflect responsibility if the accuser has many faults of their own.

We need to view sustainability as the goal, not the path. If we focus on how to integrate sustainability into design education, we will be watching the pot of water boil. If the design schools can work together on reforming the proficiency of design education by applying the design process, we can be confident in the outcome; the quality of the graduating design student will improve. If the private and nimble design schools can work together to have a positive impact on changing design education from a hierarchy to a dialogue, designers might be able to get their foot in the door of public education reform. This could ultimately integrate design thinking into public policy making.

The Council of Arts Accrediting Associations has numerous research papers on education at http://www.arts-accredit.org/. There is a reservoir of resources on ways to improve every aspect of education. The cover topics such as policy making, and the different functions of thought; historic, scientific and the art functions. These functions all need to be viewed with the same regard by society, which they are not. We all know the arts have little status in regards to science and history. Not the arts in the sense of something beautiful, but as something being created. Everybody creates every day. These functions are all embodied by the designer, but we are more intimate with them because they are all best utilized through technique. Technique is the most important aspect of education.

We as designers need to demonstrate the unbiased, objective nature of the design process. We need to appy it to ourselves and better our family of designers. We need to find a quantitative way to document the evolutions that the schools go through. Public education reform will be a battle that cannot be won if it is left to the stagnant political system. If you want something done right, you need to do it yourself; or with others who are just as passionate, otherwise you will always be compromising. Secondly, education reform is something that everyone can agree with.

please email if you want to talk more about this!!! I have soooooo much more to talk about, but as I am just a student, my words often fall on deaf ears.

miguelcastro@miad.edu