David Stairs

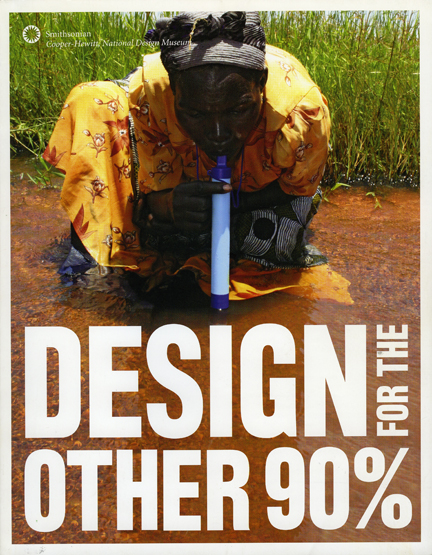

I’ve been haunted for three years by an essay I posted on Design Observer in 2007. Having just spent a year in Africa, I visited the Cooper-Hewitt while passing through New York upon my return. The exhibit that drew my attention, and fire, was Design for the Other 90%. My piece, “Why Design Won’t Save the World”, was just contrary enough to the prevailing design rhetoric that it stirred up a hornet’s nest of response, some of it really negative. The basic complaint, often coming from famous people who ought to have known better, was that I was breaking ranks by criticizing the National Design Museum. Not surprisingly, people from the developing world stood by my critique of the neo-colonialist exhibit, almost to a person.

Since 2007 things have developed apace. The sustainable design movement has caught fire with climate change now a widely accepted fact, and everybody and his brother, even IDEO, is laying claim to being socially responsible. Unfortunately, the neo-colonialist language hasn’t gotten any better. Emily Pilloton can make as many tours of the country as she likes promoting Design Revolution, but the profession-wide mantra that design, especially design by formally trained individuals from the western/northern hemispheres, will save the rest of the world is unchanged.

A couple of days ago I was contacted by Carolina Vallejo, a grad student at NYU, who has conceived an interesting project. According to Carolina, the idea came to her after she was asked to develop a socially responsible design project for the developing world on a one week deadline. She became indignant, realizing that most of the other students in the class had never traveled abroad, yet were being expected to design for people they had never met living in a place they had never visited.

What emerged was a contest called Design for the First World, an attempt to critique “the paternalistic and misinformed approaches that end up as a waste of resources and cause more harm than good in the long run.” Targeting four areas for improvement in the developed world: reducing obesity, addressing low birth rate, reducing consumption, and integrating immigrant populations, the challenge hopes to solve “First World problems” with “simple Third World solutions.”

Response to this idea has been enthusiastic, and the Dx1W Twitter feed has been buzzing for days. A part of me wants to see this initiative succeed brilliantly, but, even clever ideas have limitations. The initial premise, that the patronizing West ought to focus more attention on its own problems, is all good. It’s in the application that the idea begins to break down.

For example, promoting the idea as a contest, and an online one at that, just extends the design profession’s obsession with solving perceived “problems” through remote competition, rather than face-to-face cooperation. Vallejo defends this approach (currently 59% funded through Kickstarter) saying that attention from the art & design establishment in New York would lend legitimacy to the project overall. Personally, I feel a less conventional approach, such as a traveling exhibition in developing world capitals, or donating entry fees to select First World charities, would ultimately accomplish both ends of addressing social problems while still foregrounding talented young designers from the developing world.

Increasingly, designers from China, Brazil, India, Uganda, Colombia and elsewhere are taking their place in the world design discussion. The greater problem is not so much a matter of who is involved in the conversation as how we go about choosing our vocabulary. The language of hegemony is hard to let go, especially when cultural and economic dominance favors one group so completely. Solving First World problems is good, but it isn’t necessary or desirable to have people from the developing world imitating our flawed method. Let them show us the way to a better one.

If you’d like to make a donation to Design for the First World, please use the Kickstarter link above.

David Stairs is the editor of Design-Altruism-Project

October 13, 2010 at 5:04 pm

I do believe that it is very important to try and make a difference in the world. However, there are factors that we need to take into consideration. As important as it is to think about issues around the world in third world countries, and to pay attention to these problems, I agree that it seems crazy to think that we can easily come up with solutions to problems that exist in places many of us have never been, or know very little about. Also, certain things that we see as “problems” in the third world may not always be problems in the eyes of the people who live there. It is important to remember that even though designers can attempt to improve the lives of others in third world countries, they should be careful to remember that they may be dealing with cultures or traditions that are very important to the people in these countries. Even though design can create solutions to many problems, I am not sure that I believe that it will save the world.

The Design for the First World idea is very interesting. We have so many issues right here in our own country and other developed countries around the world. We should be doing what we can to solve these problems as well. If we cannot successfully fix so many of our own problems, what makes us think that we can fix problems all around the world? It also wouldn’t hurt us to take into consideration the opinions of those from other countries, even in the third world. Often we act like know it alls when it comes to the world’s problems. It would be interesting to see and hear the opinions that others have about our problems and the ideas they have about fixing them.

April 30, 2010 at 4:33 am

As designers interested in the social implications of our work this is a conversation that should be consistently held. I applaud David for ruffling the feathers of this movement. However, as designers we need to continue to look outside of our own profession to get a fuller understanding of our actual impact and place in the world. Too often these closed conversations lead to uniformed plaudits for design’s ability to create change–even when they start from a point of view denying that very idea. Neo-colonial overtones to social design projects is something to be understood and avoided. One way to avoid this is by partnering with grassroots organizations that represent the constituencies that design seeks to “impact”. In many cases this is exactly what Project H does.

At Design Impact, we are currently running a pilot project in India to test this very idea. Many non-profits engaged in economic development lack the resources to afford design services. As design is an essential step in technology transfer (read: making money) it makes sense that making that design can help non-profits turn their ideas into impact. From this point of view it is the non-profit, their knowledge, their resources, their networks that makes change. Design is just a tool for them to use.

-Ramsey Ford (www.d-impact.org)

April 29, 2010 at 2:49 am

While I share David’s scepticism about design’s supposed capability to save the world, I also confess to enjoying the mischieviousness of Carolina’s venture (which is why I accepted to be on her jury). Methodologically, of course any form of remotely designed intervention is less likely to succeed than a grounded one (unless backed by huge advertising type resource) and simply reversing the traditional north-designs-for-south model is no solution, not even an improvement. So what I’m looking forward to is works that play upon the ironic and critical potential of the competition theme – but I would be pleasantly surprised if I saw something even better.

April 28, 2010 at 9:02 pm

Hi David!

Thanks for the post. I completely agree with you on the idea that repeating the model is not what we should attempt, and that’s in short what the competition tries to point out with its tone and cheek tone and by mirroring the equation almost exactly.

To respond to why is this a competition, I am promoting this idea in the shape of a contest because I want it to be a platform for discussion and to get as many people as possible thinking about what does it mean to be developed and what are the problems that the developed world is facing. What i want is to create an open discussion about one world and not two or three of four. I could have designed solutions myself and then try to promote them and have them implemented, but I think it is more interesting to me to create a platform for participation and discussion, even a modest one like this contest.

As for why the exhibit is in NY and not in Accra or Bogota, I have two reasons: the first one and more superficial one is that I am in NY at the moment so it is the place I can do it. The second one is that the idea of having your work exhibited in NY is exciting for almost anyone, from the first or the third world equally. NY has visitors and residents from all over and it is a great venue for global projects to be showcased. It is not that we need the approval of NY, but the idea of exhibiting in a context where things will be seen and commented. Ideally I would love to have the exhibit itinerating, as I told you by mail the first time you inquired about this, and I have never been opposed to have it in as many places as possible. I just can’t promise that as one of the prizes cause I am not sure yet I would be able to make it happen, so I’m giving as a prize what I know I can for sure get.

Regarding the 1000 dollars for individuals or teams and not for charities. I want them to have the money, not charities, if that’s their choice then so be it, but even for me, now living in a developed country, $1000 would be a great help in my professional career. They are not going to change things much in a charity but they can bring relief to the not so well paid creative professionals, they can buy materials, software, a ticket to one of the very pricey design conferences in the first world or have a crazy party…

Critiquing the paternalistic approaches was what fired me up, and I think neocolonialism is something to be revisited by everyone, but specially by the people in the developing world. It is very very comfortable for us to have someone else to blame, but the ultimate responsibility on getting out of the mess we’re in (and I’m not saying everything we do is a mess) is ours. So my ultimate desire with the competition, or where I hope to see this idea growing is into really having an open discussion on what is the developed world that we want, and how to get there, to stop being lazy, or frightened or bullied or whatever is the feeling that is undermining our capabilities to change our own countries, to stop electing and ratifying corrupt politicians and to stop feeding the dynamic of the many worlds.

Thanks again!

C

April 28, 2010 at 7:08 pm

Emily,

First off, my comment about the “power of design” mantra was not meant to be limited to Project H, but was aimed at the profession in general. Thanks for pointing out the limits of my prose. I’ve fixed that.

I haven’t read more than excerpts of your book, and I based my comments on what I saw during your Colbert Report interview. I was also aware of your partner’s school build project in Uganda. When he introduced you Colbert didn’t use the words “save the world”, he said “fix the world.” But “save” or “fix” it’s still a greatest hits anthology approach (hippo water roller notwithstanding) to cheer leading for professional design.

I’m glad you had a good trip and met lots of people. I’m also happy to learn that you are moving to rural North Carolina to teach in a high school. Young learners are the absolute best. I agree with you that local engagement through design is the ONLY way to go. Perhaps your NC experience will result in more project and less press.

Thanks for commenting,

David Stairs

April 28, 2010 at 7:08 pm

A message for Ms. Vallejo… the third world does not need NY’s validation and neither should you. Keep up the good work.

April 28, 2010 at 6:54 pm

Designers are trained, regardless of where they received their education, to be empathetic thinkers. And being empathetic thinkers, designers can apply their knowledge and skills to a variety of problems regardless of location. To imply that people like Emily Pilloton are neo-colonialists is absurd. And using this tired, outdated language does her a disservice. You might be interested to know that she has not only worked tirelessly to address fundamental issues throughout the world, but also within our own backyard, where she is establishing a second Project H location in Bertie County, NC.

April 28, 2010 at 5:23 pm

Hi David!

Thanks for mentioning our Design Revolution in this article. (“Emily Pilloton can make as many tours of the country as she likes promoting Design Revolution, but the predictable mantra that design, especially design by formally trained professionals from the western/northern hemispheres will save the rest of the world, is unchanged.”)

I’m always open to criticism, and appreciate the mention, though I would have preferred that you actually came out to see the show, or done a bit of research before mischaracterizing the message and content of our roadshow.

If you had done so, you would have seen that very little of it is about “saving the rest of the world” so much as smart design thinking in our own back yards that sometimes comes from designers, sometimes from nondesigners and just very smart creative people. The Target prescription bottle is included, as are Montessori toys. 18 of our 22 projects (for Project H Design) are US-based public education initiatives. We never embark on projects unless we are IN THE PLACE and engaged locally. We have done only 3 international projects, and will not do any more unless we can be there for the long haul.

In fact, my partner and I are moving to the poorest county in North Carolina and getting certified as a high school teachers to run a design/build/community program for high school juniors. That you characterize this as misguided “world-saving design for the third world” is simply uninformed.

Lastly, it was no simple or easy feat to spend 75 days in an Airstream talking to 5000+ people about the power of design. It is easy to throw stones, but our adventure did result in a few great projects started, and an important dialog not just with designers but with parents, schoolchildren, passersby, business people, farmers, and more. We did this project on a shoestring budget, because we felt it was important to make the case for local engagement through design, not “design as charity.”

Let me know if you would like to discuss this further. All this being said, I do appreciate your writing and agree that the Design For The First World competition is genius and deserves serious props.

Sincerely,

Emily Pilloton

Founder, Project H Design

http://www.projecthdesign.org

http://www.designrevolutionroadshow.com