Wendy MacNaughton

In late 2000, I was offered the opportunity to create the national civic sensitization campaign for the first democratic local elections in Rwanda. The purpose of the campaign was to educate citizens (est. 8 million) about the purpose and importance of voting, teach people to use a secret ballot, and motivate everyone to participate. The campaign had to communicate equally to literate and non-literate voters, and be extremely sensitive to ethnicity and ethnic, political and economic division.

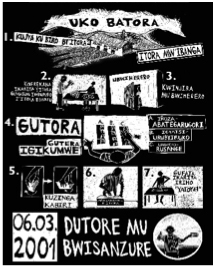

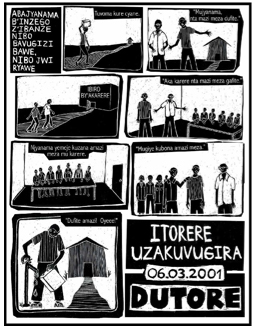

Working with the National Electoral Commission of Rwanda and United States Agency for International Development I attempted to create a campaign that was culturally relevant, ethnically sensitive and easily understood, regardless of the viewer?s level of literacy. The campaign consisted of three different mediums: posters, fliers and spray painted street graphics. With the help of cultural consultants and local businesses, I created a culturally appropriate concept, hand drew the graphics, supervised printing and organized national distribution of over 40,000 pieces of printed material.

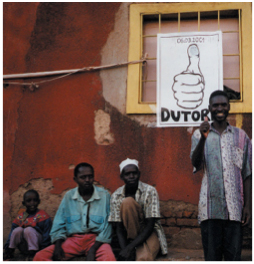

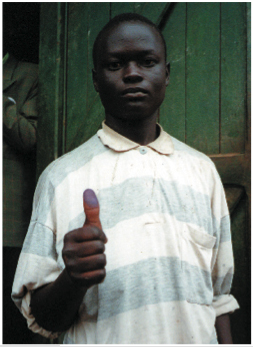

The campaign?s concept was simple. In Rwanda, most people sign official documents by stamping their thumbprint. With the introduction of the secret ballot, people would be using their thumbprints to cast their votes. I combined the image of an inked thumb with a “thumbs up” sign (which means the same thing in Rwanda as it does in the U.S.) and produced a graphic that read: voting is good. The NEC and I selected the word “Dutore” to complement the image. Translated to English, Dutore means “We Vote.” Two additional posters were created to visually communicate the process of using a secret ballot and the relevance of the local elections to people?s daily life. These posters employed a comic book technique, as this was the most familiar and effective way to communicate a narrative and avoid visual references to ethnicity. Shortly after arriving in Rwanda, I discovered that my Mac was useless. Everyone in Rwanda works on a PC and all our programs were incompatible. Furthermore, I learned that there was no money in the budget to hire a local artist to create the imagery. On top of that, it was decided that photographs should not be used as they would not fit with Rwandese visual vernacular, and their specificity in representation could signify ethnic difference. All I had left to work with were the contents of several Ziploc bags stuffed with drawing materials I had brought from home. Hoping I had enough scratch board to complete the drawings, I worked with a cultural advisor to create the subject matter, drew each image myself then worked with a local printer to layout the images.

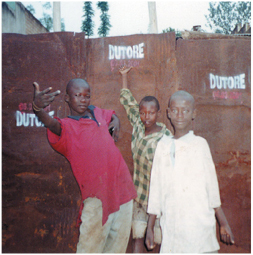

We found a local text book printer and a local copy shop in Kigali that were able to produce the posters and the fliers. About fifteen local residents were hired to hand cut the stencils for the spray paint graphics. There is no graffiti in Rwanda. In part, this is because there isn?t any spray paint. In not considering this detail beforehand, I found myself with a stack of stencils, and no paint. A man I met at a car repair shop offered to “import” the spray paint from Congo. The paints came through without a problem and luckily USAID didn?t ask too many questions.

Accustomed to buying spray-mount at the corner store, I never considered how the posters would hang on buildings and walls, let alone on trees and traditional huts. Tape and glue was scarce and too expensive to use. I shared my dilemma with a local shopkeeper from India. He suggested I make glue from a mixture of water and flour. Then I was told that sponges were too valuable to be used for gluing and that people would keep them for home use. I asked around and learned that hand brooms made of dried grass could also be used as a brush. Taking everyone?s advice, I created a visual diagram showing how to make glue from flour and a glue brush from grass and included it with the posters that were price of delivered to each prefecture.

Kigali, Rwanda is home to bands of street kids called “Maibobo.” Most were orphaned in 1994 during the genocide and have no system of support. These children are considered nuisances at best by the community as they often resort to theft to meet their needs. I had gotten to know a few of the boys and through this relationship employed a group of Maibobo to spray paint stenciled images in Kigali. The boys learned how to interact with shopkeepers in a mutually beneficial manner, made a significant contribution to society and were respected and paid for their work.

Before arriving, I worried I would not be able to graphically circumvent the ethnic and political tension in Rwanda. After leaving, I understood that it is impossible for visual communication to circumvent anything. Each and every image is layered with social, political and historical significance. This becomes obvious when one begins to work outside of one?s own visual culture. In order to create effective, relevant work, visual communicators need to learn to work cooperatively with members of the communities they are communicating to. From conception to distribution, the audience needs to participate in the creative process. If they don?t, a disempowering, top-down system of communication is perpetuated, and more than likely the work won?t communicate properly anyway.

Even something as simple as an image of a person displaying their voter registration card (as was depicted in the instructional voting poster) can have implications that an outsider would never anticipate. After election day, some people expressed strong feelings in response to this image. Apparently, the image of a person holding up their voter card recalled the ethnic identity cards used to divide Hutus and Tutsis and which were later used to target people during the genocide. People feared that the military police stationed at the voting booths might check their voter card for a stamp and look for ink on their thumb and if they were found to be without either, there could be grave consequences. When I initially learned of the reported ninety percent voter turn-out, I was thrilled. However, as I learned more about the politics of fear involved in these elections, I discovered that I might have unwittingly contributed to creating messages I did not intend. The visual is always political. It was a valuable lesson for me to learn. I just wish nobody else had to pay for it.

Wendy MacNaughton, a graduate of Art Center College and Columbia University, works at Underground in San Francisco.

October 27, 2008 at 1:26 pm

Not to mention the fact that, working for US-AID, the unintended consequences of your designs more than likely involved spreading neoliberalism and US-friendly governments; cf, the effects of “democracy” promotion in Venezuela and Bolivia.