David Stairs

A Profession, of sorts

I’ve never been a joiner. When I was eleven years old I signed up for the Boy Scouts. All my friends were in Scouts. It was the thing to do in those days. I soldiered on for three years, through weekly meetings, camping trips, merit badges, fundraisers and all. But as soon as high school came along, I was done. To this day I have an aversion to joining organizations. If you go to the end of my resumé you will not find the typical long list of affiliations common to academic CVs. Something about the Boy Scout experience stayed with me.

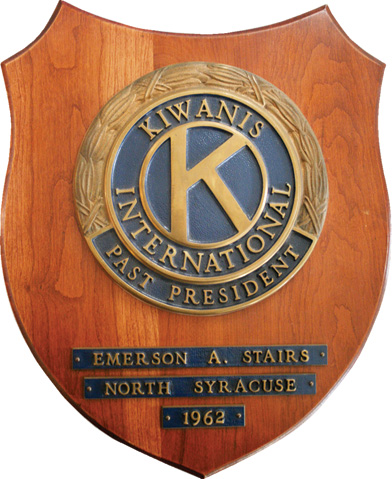

I’m not much of a recruiter, either. My Dad, a 48-year veteran of Kiwanis was much better than I. When I was first given a free professional membership for being an academic advisor, I felt compromised, especially since the reason for my membership was the recruitment of ten of my students as organization members. We academics are supposed to engage our students with professional organizations, but I began to wonder whether this sort of cheerleading was such a good idea.

In Genius and the Mobocracy Frank Lloyd Wright said: “The profession to which Louis H. Sullivan belonged, unable to value him, neglected him. But professionalism is parasitic—a body of men unable to do more than band together to protect themselves.” Now FLW was not the most generous person in the world. He could be more of a faultfinder than a soothsayer, and some of his writing suffers as a result of intolerance. That said, he never forgave the brotherhood of American architects for its treatment of Sullivan late in life. Yet, the quote has a ring of truth to it.

A number of years ago, long after I’d left the Scouts, I penned a self-righteous screed criticizing the inherent myths of expertism. I must confess, at the time I was not armed with the most credible objections, and at least one of my grad-school mentors had trouble accepting the apparent irrationality of my discontentment. More recently, while reading John Thackara’s wonderful In the Bubble, I came across his reference to Ivan Illich’s 1973 book Tools for Conviviality. Here, in 110 jam-packed pages, Illich advanced all the arguments I was lacking in my own earlier critique of professionalism. According to Illich, industrial growth and efficiency demands that man “submit to the logic of his tools.” Since it is in the nature of man’s “vital equilibrium” to resist such a dynamic, men must be manipulated by education, engineering, and bureaucracy. “People feel joy, as opposed to mere pleasure, to the extent that their activities are creative; while the growth of tools beyond a certain point increases regimentation, dependence, exploitation, and impotence.” (p. 20)

Sentiments like these owe a debt to Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on Virginia Query XIX (1782) and to the critics of the first industrial revolution, like Ruskin and Morris, who began framing the anti-industrial argument 150 years ago. Of the Crystal Palace exhibition, a young Morris claimed to have been sickened by its tastelessness. In later years he became more equivocal. InThe Revival of Handicraft (1888) Morris wrote, “As a condition of life, production by machinery is altogether an evil,” but he also had to admit, “…as an instrument for forcing on us better conditions of life it has been, and for some time yet will be, indispensable.”

By 1946, in Vision In Motion, Lazlo Moholy-Nagy was more direct. While criticizing the division of labor that relieves all workers, designers, manufacturers, and distributors of direct responsibility for the contents of products, he complained that “…irresponsibility prevails everywhere” and reserved especial disdain for professionals:

“The industrial era marks the extinction of the amateur and the arrival of the careerist, whose only aim is to commercialize the means of expression, that is, not to produce out of conviction, but merely to deliver technical skill for whatever subject is asked.” (p. 20)

ANTI-professional

Illich would see this dilemma as the result of attempts to order modern existence, efforts that replace freedom with control, and creativity with wage slavery. He felt the industrialization of any human activity created a “radical monopoly” over the activity. “Radical monopoly reflects the industrial institutionalization of values. It substitutes the standard package for the personal response. It introduces new classes of scarcity and a new device to classify people according to the level of their consumption.” (p. 54) Of this, “institutionalization of values” carries a price in the loss of autonomy. Worse yet: “The institutionalization of knowledge leads to a more general and degrading delusion. It makes people dependent on having their knowledge produced for them. It leads to a paralysis of the moral and political imagination.” (pp. 85-86)

For Illich industrialization also results in a paralysis of “independent action.” People don’t just learn what they want to know; they must be “educated.” Building codes and trades relieve them of the right to construct their own dwelling. Schools and curricula constrict independent learning. Doctors and hospitals take control of and profit from death. Morticians monopolize burial, etc. This dependence means people tend to valorize products of major institutions above those of individuals, and appreciate progressive consumption, even of intangibles like education or health care.

Illich predicted that addiction to ones’ tools would lead to a mistaken belief in unrestrained progress and a dependency upon expanding consumption. “The pooling of stores of information, the building up of a knowledge stock, the attempt to overwhelm present problems by the production of more science is the ultimate attempt to solve a crisis by escalation.” (p. 9)

One needn’t look too far beyond modern citizens chained to their workstations, entombed in their vehicles, or enthralled by their cell phones to understand what Illich means when he says that consumer society results in “prisoners of addiction” and “prisoners of envy.” In a passage far more damning than anything Wright or Moholy-Nagy ever penned, Illich indicts all professions, legal, medical, engineering and others (which should include academic) as the means by which people are made dependent in the industrial state: “The knowledge capitalism of professional imperialism subjugates people more imperceptibly than and as effectively as international finance or weaponry.” (p. 43)

In place of subjugation he offers an alternative, what he terms “conviviality.” He defines it thus: “I chose the term “conviviality” to designate the opposite of industrial productivity. I intend it to mean autonomous and creative intercourse among persons, and the intercourse of persons with their environment… I consider conviviality to be individual freedom realized in personal interdependence and, as such, an intrinsic ethical value.” (p. 11) Members of advanced industrial societies, where belief in social autonomy and economic progress results in periodic catastrophes, call this “tribalism.”

Like Morris, Illich does not rule out the use of machines. He realizes that humans are tool users. When he argues for de-professionalizing he does not imply deskilling. “Convivial tools are those which give each person who uses them the greatest opportunity to enrich the environment with the fruits of his or her vision.” (p. 21) His argument against the inefficiency of transportation methods that exceed the speed of a bicycle reminds me of David Orr’s discussion in The Nature of Design that Amish transportation is necessarily limited to the distance a horse can travel in a day. Illich is searching not for substitute artifacts, but for ways of interacting with tools that are creative rather than compulsive, what Orr terms “slow knowledge.”

Arguing against the uniformity that industrialism creates, Illich proposes an attempt to strike a balance to radical monopoly. He says that five things balance life: 1) a healthy environment, 2) a convivial economy, 3) resistance to over-programming (whether of mass manufacturing/marketing, mass transit, or mass education), 4) economic equality based upon social justice, and 5) durability rather than obsolescence. He feels society needs to be bounded, unlike in recent capitalist models, and argues that unhealthful progress needs to be inhibited. There will be obstacles to overcome, but these can be mastered through the demythologization of science, a rediscovery of language, and the recovery of legal procedure, which, Illich suggests, is complicit in the expansion of industrial control over people.

DEprofessionalize!

According to Illich’s model, underdeveloped societies, those “…in which most people depend for their goods and services on the personal whim, kindness, or skill of another” are closer to a natural state of existence than “…those in which living has been transformed into a process of ordering from an all-encompassing catalogue.” (p. 25) This observation equates well with African societies, for instance, where a majority of citizens live closer to the ground, dependent upon extended social ties and producing much of their own food.

Ironically, it is from the “developing world” that some of the best curative proposals have emerged (Illich himself worked in Mexico). When I consider deprofessionalizing, I’m drawn to Arvind Lodaya’s letter to a British design student where he says: “I think that as long as design is positioned as a ‘service’ that requires a ‘client’ with a typical ‘problem’ or ‘brief’ that she ‘solves’ using her ‘skills’, there is no way out. Unfortunately, all the well-intentioned efforts made by teachers like myself to sensitize students about the global situation and the role played by design in creating it as such etc. etc., fail as long as this model is perpetuated – even subconsciously.” When asked his opinion of this essay, Lodaya referenced Ghandi’s 1909 paper Hind Swaraj in which he proposed that a doctor “…give up his profession, and take up a handloom…” In some parts of the world this resistance to re-colonization by foreign models of practice is at least as strong as the desire for Western goods. Lodaya outlines his own ideas for a resolution of the dilemma in his cogent Agenda for a 21st Century India Report.

Professions are fundamentally aristocratic, and for members of privileged social groups to willingly renounce the prestige and affluence their positions afford is less likely now than it might have been in the hopeful 1970s. Yet, even back then Illich was unflagging in his criticism of such professions: “It is useless to expect the American Medical Association, the National Education Association, or the association of traffic engineers to explain in ordinary language the professional gangsterism of their colleagues.” (p. 98)

Is there really anything about professionalism offensive enough to warrant such invective? Isn’t it important to the establishment of best practice standards, licensure, and other things beneficial to consumers? Isn’t it dedicated to numerous forms of community service? Doesn’t it even exist in the developing world? In fact, both Rotary and Kiwanis Internationals have chapters in developing-world cities where membership is coveted as an invaluable networking tool. But even here Illich foresaw that have-nots aspire to join the highly trained hierarchies needed to monitor and control expanding industrialization.

In the design trades, which have long striven for legitimacy among their peer professions, self-redefinition for the sake of the common good is unlikely. After all, under our current system what seems more fitting than individual financial success, even if it’s at the expense of society as a whole? And who’s to determine what’s too expensive for society to bear, some wayward socialist intellectual? Furthermore, what defines the threshold of pain for an unsustainable future— Collapse of the domestic housing market? Millions of victims of global climate change? World banking chaos? Loss of the American manufacturing sector? Somali pirates? We already coexist with these realities and, if we don’t think about Moholy-Nagy too much, we can pass the responsibility on to future generations and carry on in the comfort of insider affiliation very well indeed.

Cutting the professional safety net can seem like cutting the ground from under the feet of people over-invested in the dominant system. The AIGA’s current Aspen Design Challenge (a collaboration with INDEX) epitomizes this system: engage students in top-down design contests to address large-scale developing-world problems. But Illich saw through this with a clever analogy when he wrote: “Deprofessionalization means a renewed distinction between the freedom of vocation and the occasional boost sick people derive from the quasi-religious authority of the certified doctor.”(p. 36)

If our society aspires to truly address its problems with something more potent than platitudes and design contests, it will require real sacrifice— the kind that substitutes other for self, and true imagination for lock-step networking. At times the best course of action demands more than complete dependence, more even than radical independence. Sometimes the best solution for a healthy society is non-aggrandizing interdependence, despite the risk of lost authority and increased social entanglement, contrary to predictable norms, contraindicated by conventional wisdom. In other words, when it comes to scouting, neither a joiner nor a recruiter be. That’s a loose paraphrase of the original attributed to Shakespeare’s Polonius, who, while he may well have been a professional aristocrat, was definitely not a budding Kiwanian.

David Stairs is editor of Design-Altruism-Project.

Special thanks to both Arvind Lodaya and Wes Janz for their many suggestions that helped to improve this essay.

January 15, 2009 at 3:03 pm

Fred, you’re a good man (any CMU grad is a solid person in my mind) who, along with the rest of us, is learning and growing everyday. Do not take my tone as being negative but rather as that voice who always tries to look at the positive and negative to everything. Take the iPod touch again. No doubt it is a great device, but I wonder what I’ll be doing with it in 5 years. Most likely I’ll turn it back into Apple to recycle. From Apple the iPod will then travel to some third world country where environmental issues are not a concern and it will be stripped of it’s parts, melted down to the basic items and “recycled” to be used in some other technology wonder of the time, all the while polluting the environment with the toxic excess and causing severe harm to the worker(s) who have the task of performing such a job. The same “recycling” fate can be said for all those wonderful computers we all use, along with their fantastic 30″ monitors and even those fancy and must have 62″ LCD HDTV’s (of which I have 2).

What is my point to this? Not sure, just wanted to point out how wonderful technology is and how once we buy the product, we are helping pollute some country far, far away. Maybe some day the technology bean counters will figure things out and forget about the bottom line and create a product that will last a bit longer and not have to be replaced every 2 years. Or even better, we as consumers will demand products that last and can easily be upgraded every 5, 7, 10, 25 years. Just a thought. Anyway, Fred, I was way off the topic on this one but just wanted to say keep up the struggle. Below are some nice links that discuss the technology recycling problem.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/1839997.stm

http://abcnews.go.com/2020/Technology/story?id=1479506

p.s. And one more note, there is no doubt in my mind that those who work with nature, live with nature, and depend on nature are more in tune with nature than I am, and I appreciate that.

January 14, 2009 at 3:11 am

Hey Koz, that was a great article. Bean counting indeed! “Creating a graphic language with today’s tools will mean forgetting the styles of archaic technologies and remembering the very basic of design principles.” It’s the same sort of argument we’ve been talking about for forever, but it seems the ante is upped more often than, at least, I realize… It’s definitely the submittal to the logic of man’s tools. That article could bring up some great discussion, but I don’t want to trail any further than I already have…

First off, I would definitely like to apologize for the tone I used up there- Like I said, a lot of this stuff really hit home for me, and I got so excited about my response that I didn’t read it before submitting it, and definitely wasn’t aware of what an ass I feel I sounded like.

*Obviously* the iPod Touch and iPhone are remarkable tools- my friend Phil uses his in a similar style as you mentioned and it’s definitely come in handy. But I’m still pretty fresh out of college, and even still, whenever I hear someone say something like, “I am connected to my iPod and you can’t take it away,” I can’t help but remember all the drones walking around me all over campus plugged into their iPods. Really, to each his own, and certainly satisfaction can be achieved through this. Now, I don’t know you, I didn’t know what you used it for, and it’s none of my business anyway. But I mentioned the spur-of-the-moment selling of my iPod because, as of late, I’ve been trying to rid myself of all (ideally all, at least) possessions that are not “convivial tools.” “Convivial tools are those which give each person who uses them the greatest opportunity to enrich the environment with the fruits of his or her vision.” For me, while it is certainly a useful tool, an iPod Touch does not give me what I need to do this, so I ousted it. Again, it’s just personal. It fits others’ uses better than my own. Travelling’s more important to me, so I swapped it. But it just happened to happen last week so I jumped on mentioning it. Just to clarify.

Definitely not every “third world” country lives in total harmony with nature and is completely conscious of her well-being. In Uganda they raise livestock in crowded *medians* of dusty traffic-infested roads. Garbage of all kind piles several stories high at times, and is on the sides of roads everywhere, waiting to be carelessly burned by its producers. The exploitation of natural resources is more than prevalent. But at the same time, there is a certain level of intuition- telepathic, almost literally- that I experienced out there, that could never have coexisted within someone plugged into their iPod. There is truly an undeniable level of connectedness to nature exhibited by someone working in the fields all day, making all their meals outside from mostly their own harvest, socially interacting mainly out-of-doors and sleeping in uninsulated shacks of mud, all their life, for generations upon generations. –Such connectedness that said people would find difficulty comprehending the usefulness of an iPod Touch or a MacBook Pro. Destroying the environment, or the physical interaction with the earth is not entirely what I was referring to. In my experience, these people “living closer to the ground” are more naturally attuned to we as a species and in many ways have become more intuitively-sound where we have become more technologically-sound.

Has nothing to do with the Boy Scouts, but was in response to David’s first paragraph under the “DEprofessionalize!” section.

January 13, 2009 at 5:47 pm

Hi David,

Best wishes for the new year. I finally got around reading your wonderful post.

I cannot tell you how much your key points resonate with me. Needing to deal with constant uprooting as a diplomat’s kid, I quickly developed a certain resiliency that has allowed me to welcome– if not seek—change as a positive, and with that, I have also come to cherish living my life with openness and a endless sense of curiosity. Professionally in the past years, that has translated of course in discovering that those aptitudes and skills were very effective tools for me to access in getting the Designmatters program going.

In retrospect, I am quite proud with our trajectory these past seven years, and I realize now how much the creative, open scout, entrepreneurial spirit that I relied on, and that others had around me, has paid off.

I love your phrase: “when it comes to scouting, neither a recruiter nor a joiner be.”

As I ponder the future of Designmatters, after the program’s significant growth in the last year, but also at this time of leadership transition at the college, your words give me the clarity and strength to keep that scout spirit alive.

For that I thank you!

Best

Mariana

ps: hey, full disclosure: I agreed to support a class that did work on the AIGA/Index water call. It will not be a surprise to you that a more modest effort with an independent study project that allowed students to work in Guatemala in a rural community stands a real chance of being the “real deal” intervention….

January 13, 2009 at 3:14 pm

Hunters and gatherers…….I like that. But what about the ones who cook and those who clean? What groups do they fit in? Are they known as the cookers/cleaners or do the hunters and gatherers have to pull double duty? What about the leader who tells the groups to hunt and gather? Does the Boy Scouts teach about these different groups? Not sure since I never joined. Anyway, I think it is important to the artist who is doing the design to be comfortable with what work they are producing. Functionality is a major factor in design but sometimes, maybe the aesthetic of beautiful design is more important than functionality. And in other cases, maybe functionality is more important than strictly beautiful design. And in the whole mother of all designs – functionality and beauty live in harmony. This all depends on the designer, the client, the project, what kind of coffee is in the cup, how fast the MacPro is running, the alignment of the stars and many other major factors 🙂

I believe “third world” countries also live in different societies and different classes just as higher societies do. To group all “third world” countries together is tough to do. Yes, some “third world” countries are more in tune with nature then say the Russia or China. But others I would argue destroy the environment around them and are not at one with nature. But I am not sure what that has to do with design or with joining the Boy Scouts. Just throwing my two cents in on this argument.

Fred, I am glad that you were able to get out and enjoy a trip to Chicago. I always enjoy spending time in the windy city. And I am glad you were able to part with your iPod to help pay for the trip. I too took a spur-of-the-moment trip to Arizona in the fall to do some backpacking in the mountains. The day before my trip I decided to purchase an iPod touch. Glad I did. Being at one with nature sometimes has it’s upsides and sometimes it can be down right too peaceful. I enjoyed the fact that on one of our hikes, we stumbled upon a ranger station that had wi-fi. Nothing like being at one with nature and being able to approve a pdf proof 5000 feet up a mountain with a deer 10 feet away!

Anyway, here is to bean-counting 101 and all the discussion that it shall bring:

http://www.emigre.com/Editorial.php?sect=1&id=19

January 11, 2009 at 10:42 pm

I really can’t put into words how glad I am to be reading this at the point I’m at right now, today. I feel as though I’ve been contemplating many of these exact thoughts for a couple of months now and it has definitely helped direct my train of thought.

I think a main point to consider is made about halfway through, regarding underdeveloped societies’ state of existence being more natural than the highly-industrialized society. It really goes as far back as pre-hunters and gatherers. At some point, someone said, “Ok, this group will hunt, and this group will tend to the harvest.” “Ok, now half of you hunters will hunt this kind of animal, half will hunt this other kind.” And it keeps splitting off into these specialties and you eventually get the artisans- the blacksmiths and the candlestick makers, and finally there’s some poor guy in a cellar somewhere who’s been assigned to count beans for the king. And how does this directly affect his survival? He’s counting beans! And thousands of years later we are so much more removed that it’s even hard to *imagine* such a society where the fruits of our labors directly affect our survival. Such societies mainly exist under the label, “Third World.” And yet these peoples are infinitely more attuned to the world around them and the earth from which they were born.

Deprofessionalization. I like this idea a lot.

PS, I just sold my iPod Touch last week. I used the money to pay for a spur-of-the-moment urban backpacking trip to Chicago. I’m confused by Koz’ statement up there. You’re in constant battle with the non-design-types you work for because you’re not doing what they want, but instead designing solely for the beauty for design?

This is actually something I’m struggling with as of late. The “client/problem/brief” issue. It’s a service using these elaborate tools. Certainly can be important on many levels, yet is very much bean counting.

I seek to utilize design for the antithesis of the “design for the beauty of design” argument. What does that mean, anyway? Is functionality not a factor??

Bring on the discomfort! That’s where we’ll learn what we REALLY can do to make social change.

December 20, 2008 at 1:41 am

I think your discussion of the Post-Professional presents an interesting hypothesis to those of us interested in the forms and formation of society and culture, but to suggest a possible solution to our societies’ malaise would be to disband groups comes across as a knee-jerk reaction that is too unconventional to put substantial weight behind. I wonder if your idea may be better off as a critique of the group mentality elevated to professional status. I only say this because I’m developing a working model of humanity (impossible, yes, I know) and it’s relationship to a graphic designers mentality – not for any project, just from gathering, note-taking, etc. In this nebulous model, I find arguments such as the one you present need to continually return to a belief that humanity isn’t out to best one another, which I don’t believe is true. The majority of persons trying to find their place in this world will quickly find allegiance to certain groups while abhorring others, whether they be professional in nature or casual; it’s just the way life works. I think ignoring this leaves a hole in the argument.

December 19, 2008 at 8:24 am

So I skimmed this super fast, reading more of the last paragraph than that which supported the whole of the essay. Hopefully I don’t sound too ignorant.

Design, just like any other profession is geared toward maintaining hierarchy and over-compartmentalizing our work habits and environments for the sake of profit. It all about productivity. Nobody wants a trainee or an intern these days. They want the skilled cello and woodwind players they hire to fit in harmoniously with their personal symphony. They don’t want thinkers, they don’t even want to be thoughtful.

The act of creating work is more of a defensive strategy, than an offensive or progressive one. Whether we’re working for a corporate client or a non-profit fighting cancer, its for the recognition, the networking opps and more so just to feed our gluttonous egos. Sure it has a functional purpose as we live in a monetary run society, but with all the sustainability minded, liberty loving that is going on post Yes We Can, I don’t see many inviting others into their nest vs. fending off predators.

Joining the aristocracy is always accompanied by a blinding light. Its what we think we should do and how we should act. Though I think humans are more inclined to be collaborative and community based, even this has been corrupted by attaching the promise of glory and status, however minute, to new levels of self-aggrandizing. There are very few that practice true altruism because it does require sacrifice that few of us have ever had to give. And most aren’t prepared or brave enough to make themselves uncomfortable.

December 17, 2008 at 9:54 pm

No one shall take my iPod Touch from me! I am connected to it and it to me. The rise of the machines is coming….Nice essay Stairs. A little too professional for me, with all the foot notes and references (LOL). “…I’m drawn to Arvind Lodaya’s letter to a British design student where he says: ‘I think that as long as design is positioned as a ’service’ that requires a ‘client’ with a typical ‘problem’ or ‘brief’ that she ’solves’ using her ’skills’, there is no way out…” This explains why I (Koz) am in a constant battle with those I work for (non design types). I never design for their end (the end all, be all obvious solution – a Word document), but rather, I design for the beauty of design. More up and coming designers should take this article to heart. Kudos to you David Stairs for not being a group joiner.