David Stairs

I was recently in Austria where I delivered a lecture in Graz during Graz Design Month.

The thing most striking about traveling in Central Europe is the sense of the past preserved. The cities of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire survived WWII better than their German counterparts, having been at the outer range of the RAF/Eighth Air Force sorties. Consequently, the old blends in with the new quite well. In fact, the Art Museum in Graz is a hybrid of combined buildings.

One can’t help but appreciate the public transit systems. In the towns, tramcars are everywhere. Between cities and suburbs a system of light rail is an available alternative to car ownership. My Prague friends have not owned a car since 2003. Although their children might lament the fact, the family is still able to get around.

The rail system in Austria is a wonder, quietly efficient in a way unknown in America for more than a century. It is easy to make reservations online, with the site being accessible in both German and English. Most of the trains are powered by electricity. The trains not only run silently, but also on time.

The street graphics in Vienna run the gamut from expensive corporately produced posters to every sort of graffiti imaginable. Much of the street art is the usual teen tagging, colorful and expressive, but some, like this stenciled mirrored figure, speak with mute eloquence of the frustration with officialdom.

The Viennese skyline is impressive. 18th century apartments mix with post-war construction. The steeples of churches, both orthodox and roman, dot the horizon. There are mosques, too. It was not possible to see the Riesenrad or large Ferris wheel made famous in 1949’s The Third Man from the roof of my friend’s apartment, but the telecommunications tower, now relegated to sending radiowaves, was prominent.

Everywhere street-level vending machines have been incorporated into building facades. Recycling bins are conveniently located on street corners, and the streets are preternaturally clean. Even the fireplugs make one aware of being in a foreign place. This example of iron railing by Otto Wagner is like what can be found running for kilometers along the Danube through the city’s center.

The trappings of empire are easily found. Prince Eugen, victor over the Turks at the Battle of Zenta in 1697, built the Belvedere Palace in the 18th century. Now a very popular Klimt museum and formal garden, it is walking distance from my friends’ flat in Kolbgasse.

Also within easy walking range is one of the remaining “Flakturms” or famous antiaircraft batteries erected by the Luftwaffe. These awesome concrete structures formerly housed searchlights and antiaircraft cannons. Two of them currently serve as alternate art sites for work by James Turrell and Jenny Holzer.

The Leopold Museum featured numerous pieces from the turn of the 20th century when the Wiener Werkstatte and its famous practitioners, Koloman Mosher and Josef Hoffmann, were active. Icons of 20th century furniture design, like Hoffmann’s “machine for sitting” were prominently displayed.

Not far away, at the Museum of the Vienna Sessession, Gustav Klimt’s lovely Beethoven Frieze is on permanent loan from the Belevedere. The basement room where the frieze is displayed, feeling more like a chapel than museum, was filled with students dutifully sketching. Amazingly, Klimt, Wagner, and Egon Schiele all died in the terrible Spanish Flu year of 1918.

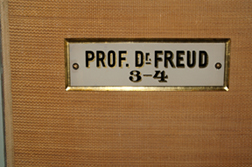

And what trip to Vienna would be complete without a visit to Sigmund Freud’s former abode at 19 Bergstrasse? The museum has a bookshop, library, collection of artworks, and several rooms of artifacts and reproductions, including Dr. Freud’s original doorplate.

In 1910 Vienna was the fourth most populous city on earth. Today, its population has declined a little from its pre-WWI peak, but it has lost none of the charm, elegance, or design of its fin de siècle imperial days.

David Stairs is the founding editor of Design-Altruism-Project

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.