David Stairs

It happened in an instant.

One moment I was leaving the school parking lot, the next the ground was close to my face and I could see the EMT’s feet as they worked around me. It was 8:20am Monday May 2. Moments earlier I had dropped my son Luco off at Renaissance Public School Academy, a charter school located on Isabella Road in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. It’s a fast road, 45mph, with no speed zone for the school. I’d left this parking lot thousands of times and never taken it lightly. In the mornings and after school there could be hundreds of cars turning in and out. It was treacherous, even when there was no ice on the ground. On this day the two cars in front of me left together. Drivers have so much respect for the speeds here that they don’t even observe the appropriate traffic rules. As I looked to my left I saw a vehicle signaling to enter the parking lot 200 feet further south. Safe there. On my right a vehicle was making a right turn to exit the lot while I waited to make a left. I couldn’t see around him, so I waited a couple seconds for a clear view. Southbound traffic was approaching fast; If I moved now I’d have time to clear the line of left hand turners in the middle lane out on the road waiting to get into the lot. I went. That’s when time began to slow. As I looked left again I realized that a vehicle had been masked by the turning car on my left, was approaching me at full speed, and I’d pulled right out in front of it. I didn’t hear the impact but clearly remember the thought of my own scream, “This can’t be happening!” Only the night before I’d been congratulating myself on 42 years of collision-free driving. I remember thinking I needed to get away, to get free of the embarrassing wreck, so I moved my legs and slid across the passenger’s seat and opened the door. The next thing I remember was people asking me polite questions, “What’s your name, sir?” “Who are your next of kin?” As they strapped me to a board and shoved me into the ambulance the school principal stood nearby shedding huge tears. Earlier this year she had been rejected by the county road commission in her bid to get a school speed-zone established on this stretch of road.

What was left of my ’09 Prius

I was rushed to the local hospital, about five minutes away, where I was cited for failure to yield by the deputy sheriff, and asked more of the same questions by an ever widening cast of characters. “Did I need them to call anyone?” “Who could they contact to provide for my son?” “Where did it hurt?” And, of course, “Was I allergic to anything?” I was gang-hoisted from a backing board to a CT scanner to a gurney to an x-ray bed. After awhile the ER intake resident came back. I had a cracked pelvis and an injured spleen. He told me that he was arranging transfer for me because the CT indicated there was internal bleeding, the local hospital was not equipped to monitor me, and he couldn’t keep me with the risk I might “bleed out.” He couldn’t find space at the nearest trauma center, so he was arranging transfer to one 90 miles away and I’d be taken by helicopter. Looking forward to my first chopper ride I soon realized I’d been demoted to an ambulance. I was catheterized and rolled back outside. As the vehicle left the ER dock I lay strapped to a board in a head harness thinking I might go crazy over the next two hours. The attendants kept asking whether there was anything they could do to make me comfortable. “No, they hadn’t been cleared to remove the head harness,” even though there had been no indication at the hospital that I’d suffered head or neck trauma. My face was abraded from my fall to the pavement, but with a side impact, the front airbags had not even deployed. “Could I have a drink?” My mouth was so dry it tasted like carpet. “No, I was on an IV, and they hadn’t been cleared to give me anything to drink.” But they did swab my mouth. Every few minutes the blood pressure band automatically inflated. The road was bumpy; the small talk related to previous first-responder experiences.

What happened when I passed out and face-planted exiting my car

After what seemed like eons we arrived at the trauma center. Now I was really in “the system,” the massively redundant vertically integrated chain-of-command bureaucracy that, in America, passes for emergency health care. It’s a world where nurses don’t breathe unless doctors tell them to, and doctors don’t make decisions unless supported by reams of medical imaging and lab data. Again the many questions about name, insurance, allergies, health history, sequence of events were asked at every stage. The ER team cut my shirts off, even though my sweatshirt had a zipper. Three hours had elapsed since the accident and I was still in a head harness. “Was I in pain? Would I like any pain relief?” Would I! This was the first time it had been offered. Before I could be admitted to a semi-private room on the trauma ward upstairs there would need to be more X-rays, these of my pelvis. Could I have the head harness removed? “No, it hadn’t been cleared yet,” came the now familiar refrain. “One. Two. Three, lift!” Back onto the cold hard bed of a radiological table. I was beginning to drift. The pain-killer was kicking in.

Sometime later I awoke to find myself in a semi-private room on the fourth floor. Everyone seemed to be about thirty years old. People’s Court was blaring on my room mate’s television. A steady stream of on-duty resident physicians passed through the room. To each I recited my litany of familiar responses. There was the Trauma Team; the Ortho Team; the Lab Team. By my estimate, over the course of the next two days I’d be exposed to at least fifty different medical professionals, including nursing staff. The specialists made their appearance: the Social Worker; the Physical Therapist; The Speech Pathologist. “Did I want to see a clergyman?” Nurses were constantly hovering when not wanted and hard to find when needed. At all hours, whether sleeping or waking, technicians appeared to draw blood and “check vitals.” If I’d never before felt part of a giant Borg-like mechanism, I was certainly getting my chance.

Pain meds are only a scan away

The man in the bed next to mine was a mess. A 73 year-old African American male, he’d been admitted for e-coli sepsis. He complained regularly about feeling nauseous, but no one checked his meals very carefully. Instead, he was fed intravenous anti-nausea meds. One night he needed a nurse but couldn’t find his call button. I contacted the nurse’s station on mine explaining he needed to get to the john. Nursing staff showed up about ten minutes later, after he’d soiled himself. Hospital food is the stuff of legend, of course, but it’s the way it is distributed that really should be reviewed. My first night I didn’t eat dinner. Although my doctor had ordered it for me, it never showed up. Not a problem. I wasn’t hungry. I requested a cup of yogurt; it took the staff three quarters of an hour to deliver it. Next day breakfast appeared in the form of a ham omlette and sides. None of the food on the tray was real evil, but I hadn’t eaten for a day and a half, and none of it was appropriate for breaking a 36 hour fast. Ditto the turkey and Canadian bacon wrap that appeared for lunch. My second afternoon I received a call inquiring about my choices for dinner and breakfast. This was an improvement and, while canned peaches aren’t anything to crow about, at least I could look at them. On my second day I was on the phone much of the time, talking to family, starting the insurance claim process, arranging for my final classes. It was finals week, and I’d gotten the reputation on the ward as “the guy who needed to be released Wednesday so he could proctor an exam.”

I had my first physical therapy adventure at this time. Specialist Brandon gave me a lesson in how to use crutches, and we limped down the hall to the four-steps-and-a-railing test. I was weak, and my breathing was labored. My blood oxygen level plummeted. Despite this, a doctor asked me whether I wanted to “go home today.” I said I thought I probably ought to spend one more night, although the prospect did not excite me. My first night I had been given morphine, but this had been removed the second day, when I didn’t get much pain medicine at all. Around 3pm I requested a Tylenol for headache, likely brought on by pain, and when a physician asked me if I needed painkiller, I said I probably should wait until bedtime so I could sleep. He told me enduring pain leads to other forms of stress, and I probably should have something. At 6pm I was given a Vicodin, Tylenol souped up with codeine.

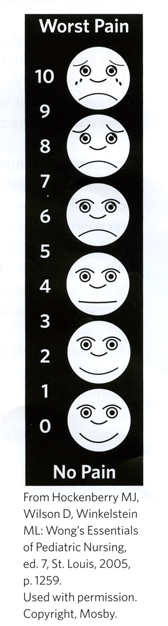

The greatest pain was this graphic

One of the questions most frequently asked in the hospital is, “On a scale of 1 to 10, what’s your pain level?” Now, this is relative, and is treated as such. Some people report level 4 pain as being “13” and it’s acknowledged to be a very subjective scale. But it can determine what’s prescribed and when. I’m not crazy about painkillers, and I try to wean myself from them quickly. By my estimation, my pain never rose above a 5, and no one seemed too concerned about it as a result. No wonder! On the hospital’s pain monitor graphic, 5 resembles a normal face at rest. By day three I was itching to get out. I’d been cleared by Ortho, but the Trauma Team was withholding approval pending my blood oxygen levels. A couple nights of shallow breathing on my back while being fed O2 had me slightly congested. The Respiratory Team arrived to talk to me about inhalers. It seems two days is all it takes to make an injured but otherwise healthy person a candidate for pneumonia in todays’ hospitals. I finally understood why so many elderly people never return from their brush with “the system.” I commenced running up and down the halls on my crutches, hyperventilating into a tube to eventually convince doctors I was fit to leave. During my busy Tuesday I was visited by a nurse who acts as a contract manager for people needing to set up home health care, or do living space analysis after an accident. This enabled me to have certain things, like shower seats and a wheelchair, in place when I arrived home. I didn’t know it at the time, but she was one of the first of at least eight insurance professionals I’d have to deal with in the coming weeks.

What I am discovering about equipment for trauma patients is that the default isn’t very smart. Take my crutches, for example. Shiny aluminum made-in-China traditional design, they are prone to tip over, don’t help much in reaching, and have no hooks or pouches for carrying in the mail or replacing the TP. Ditto wheelchairs. They fold and have wheels for hand driving, and anti-tip mechanisms, but any trays or cup holders for moving food and drink, while available, are considered accessories. Not to mention the usefulness of a clip for crutches.

Jury-rigged equipment

Every visit by every medical professional while in hospital, whether it’s necessary or not, is billed at an exorbitant rate. A visit to the ER: $1,100. Semi-Private room on the trauma ward: $1225 per day. Ninety minutes of physical therapy: $510. An interview with occupational therapy: $374. Speech therapist (even though I’d not been diagnosed with head trauma) $427. The Lab charged me twice, once for lab services, $264, and once for hematology, $188. Total charge for 48 hours: $6733. Put $1300 atop that for ambulances. Add another $651 from the referring institution and you have a grand total of $8684. Funny thing is, a patient has the right to reject, or at least be informed about all this “extra” service. At one point I’d complained to a physician about how my midriff felt like it had been clubbed with a baseball bat— I had been in an accident, after all! He quickly arranged for an additional chest x-ray, “Just to make certain they hadn’t missed anything.” I told the technicians when they arrived that the doctor had taken my comment out of context, that I didn’t want to return to the cold x-ray machine, and I reiterated this when the doctor later returned to ask me what was happening. The upshot: no x-ray.

A crutch holster would be welcome

Overall, I’ve learned a lot from my one-second mistake leaving the school driveway. For all its vaunted technology, our grotesquely for-profit health care system is neither smart nor efficient. EMT’s couldn’t steady my head before stopping to slip on a pair of latex gloves. I spent nine hours in a head harness because two hospitals couldn’t interface through layers of HIPPA bureaucracy to FTP a CT scan from one to the other. I found hospital nutrition loaded with carbs and hard to digest proteins, with a diuretic like coffee automatically served to most patients. Nighttime nursing staff was either incredibly invasive, waking patients in order to keep to a rounds schedule, or unavailable at critical moments. Where there was a direct correlation between pain and recovery, I found the dispensation of pain relief lax and ad hoc. I was told at one point that the nurse would have given me pain relief if I had asked when what I needed was a strict regimen. And I observed others around me treated for their immediate symptoms, with little or no oversight for their general well being. I suspect the reasons for these failures at a trauma center are many, not least of all that I’m an acutely critical patient. Mostly, though, what I found lacking was simple humanity. Here were highly trained people going about their duties in a dispassionate way, some quietly efficient, others annoyingly invasive. But when you are sore and frustrated and wanting to be home, having a person cheerily introduce themselves at 7am for physical therapy just doesn’t cut it. I met many smart people working in that hospital, but only one who possessed the quality I’d consider pre-eminent to patient care: compassion.

When I was a child I had a wonderful pediatrician named Dr. Roberts. He’s still practicing nearly 70 years after leaving med school. I remember him visiting our home a few times during childhood illnesses my brothers and I suffered. Even an office visit for a shot was not too horrible an experience, because Dr. Roberts’ manner was so gentle and considerate that he inspired great confidence. If I were to redesign our flawed trauma care system, that’s where I’d start. For a system obsessed with exploiting the insurance system and avoiding malpractice litigation, I’d prescribe a pair of warm hands. Its been said before and I suppose will be said again, if we hope to get a handle on our tottering and inefficient health care system, it won’t be as a result of electronic records keeping or new surgical techniques, but through a combination of careful cost accounting and good old fashioned hand holding. At the moment, that only happens cautiously, distantly, through a mediating line-item pair of 59¢ latex gloves. We can do better.

David Stairs is the founding editor of Design-Altruism-Project

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.