Daniel Drennan ElAwar

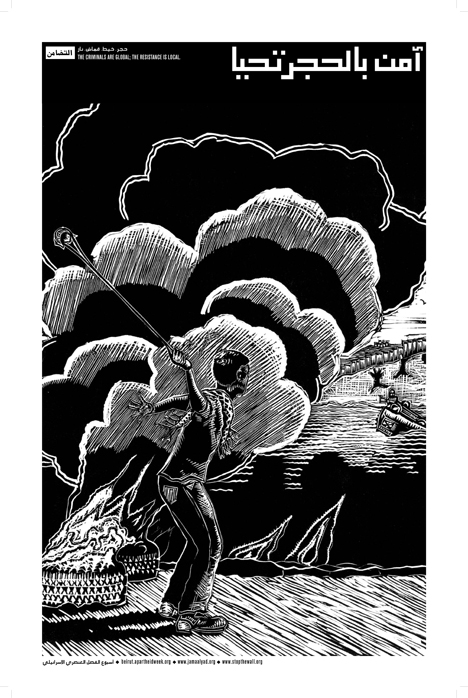

“Believe in stone and survive.”

Framework

From the Declaration of the Palestinian People during the first intifada in 1987:

We will no longer be a subject people. If you order us to our camps, we will roam the countryside. Dig up our soil and bury us alive in it if you will. If you direct us to work in your factories, we will confine ourselves to our homes. Herd us into concentration camps if you will. If you instruct us to buy your produce and your products, we will grow and make our own.

We are currently witnessing a critical mass of global movements coming together and organizing their efforts at boycotting, divesting from, and sanctioning Israeli apartheid. In order to understand the impetus behind these efforts, it might be worth understanding, historically speaking, the effort that went in to doing the exact opposite: promoting the state of Israel as a homeland for the Jewish diaspora, since Palestine was just one of many possible destinations for Jews after the Jewish holocaust of World War II.

The “selling” of Palestine as a Jewish homeland is interesting for a variety of reasons. First, the anti-Semitism of both Axis and Allied forces during World War II was a foundational premise to a further ridding of the “modern” world of its Jewry, with Zionists as accomplices. Second, the resulting second-class treatment of actual Arab Jews, Mizrahim, and Sephardim, which has its counterpart in the racism suffered by Ethiopian Jews in their supposed homeland, forms a sort of “unity of the displaced” among those mistreated by the Israeli regime. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, because the basic premises of the Zionist endeavor acknowledged what was then known as and referred to as Palestine.

This can be seen in the “Visit Palestine” poster from the Tourist Association of Palestine, a Zionist development agency. Quoting from Liberation Graphics:

With this one poster pulled out of the Zionist attic, three core myths are debunked. The first myth is that Palestine had ever been a land without people. Obviously someone lived in these houses and someone tended these gardens. The second myth is that Palestine was a vast desert awaiting cultivation. The resplendent tree in the foreground suggests that the land surrounding Jerusalem was much more than barren desert. The third myth is that there never was a Palestine. Of course there was a Palestine, and here it is, called by name in a Zionist-published poster.

This poster stands in precursive contradiction to the decades of attempts via mediation, academic intervention, and other forms of mythologizing to “erase” Palestine and the Palestinian people, as seen in this example from Al-Khalil (known as Hebron). It stands in new settler colonies, and reads: “Palestine Never Existed (and Never Will).”

“He who digs a trap falls into it.”

Compared to Zionist development efforts, the claim that the BDS movement is rather recent is true; it dates to 2005 and the official “Palestinian Civil Society Calls for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against Israel Until it Complies with International Law and Universal Principles of Human Rights”. Nonetheless, the concept of BDS itself goes back to the efforts waged to bring South Africa in line with international norms. It is a great irony to realize that in 1975 these two countries signed the Israel/South Africa Agreement (ISSA). Today, a neo-liberalized South Africa provides what can only be referred to as “apartheid know-how” to Israeli occupation efforts.

The roots of BDS in terms of activism run deep. For one example, a poster from the Bay Area–artist Juan Fuentes from 1974 speaks to the racist underpinnings of Zionist ideology, as condemned at the time by the United Nations. A great resource for both the Zionist efforts to promote Palestine/Israel as a homeland, and on the other hand, to speak of the human rights of the Palestinian people existing both in the occupied state of Palestine, as well as living as refugees in neighboring nation-states, can be found at the Palestinian Poster Project Archive. Its archives, balanced between these two sides, ironically manage to state quite strongly the Palestinian case.

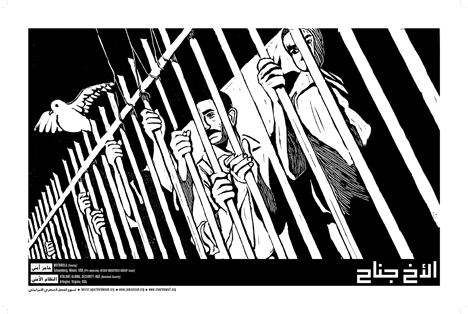

“My brother [is] my wing.”

The comparison to apartheid South Africa is crucial for a variety of reasons, and is probably best left to those who experienced and lived that struggle. For one example, in a letter to the Congress of South African Trade Unions in 2009, Zwelinzima Vavi spells out very clearly the similarities between South African apartheid and the current situation in occupied Palestine. He states:

From our own experience, we know how painful and dehumanizing is the system of segregation, otherwise known as apartheid….What other definition would so fittingly define a system based on different rights and privileges for Jews and Arabs in the Middle East? The bantustanization of Palestine into pieces or strips West Bank, Ramallah, Gaza Strip and so on run by Israel and with no rights whatsoever for the Palestinians, is definitely an apartheid system.

He would later (rather distressingly) clarify this position in an address to the Russell Tribunal on Palestine:

Palestinian workers do not fulfill the same purpose for apartheid Israel as Black workers did for apartheid South Africa, and they are not exploited in the same manner as Black workers were. Nevertheless, Palestinian workers and the Palestinian working class are, as Black workers and the Black working class in South Africa were, oppressed and exploited simply because of their “racial” and “ethnic” background. As apartheid South Africa attempted to do with the Black working class, apartheid Israel too seeks to humiliate and degrade the Palestinian working class, robbing it of its dignity and attempting to beat it into submission to a cruel, racist system. There are two major differences between the situation we faced under apartheid, and that which Palestinian workers and the Palestinian working class face under Zionist Israel. First, that while the South African apartheid state and White capital remained till the very end entirely dependent on Black labour, the Israeli state and Israeli capitalism have divested themselves of this dependency. Second, and following on the first, is that while in apartheid South Africa the state attempted to keep Black people “in their place” so they could be pliant workers that were easy to exploit, the apartheid Israeli state wishes to ethnically cleanse the Palestinian working class and the Palestinian people more generally.

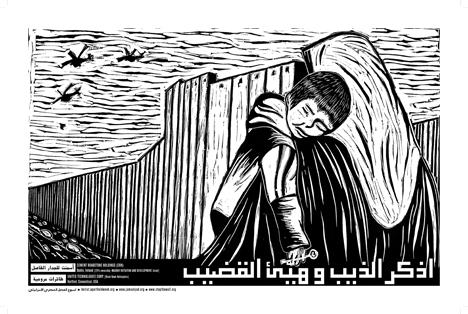

“Where can the wolf hide in broad daylight?”

In this light, the imperative to boycott, divest, and sanction grows even greater. Recent mediation of the scandal involving Scarlett Johansson, spokesperson for the Soda Stream company located in the occupied West Bank, along with a growing academic effort to enact BDS as an activist stance, has brought the BDS movement to the fore of global attention. Even the Israeli press is stating the case, as in this editorial from Carolina Landsmann in Haaretz:

That is also the tragedy of Oslo. The revolution was not completed. It was interrupted. And the attitude toward the Arabs remained the same, and even deteriorated. Just as Martin Luther King understood that there is a line connecting the blacks in the United States with those in South Africa, and that the former would not be free until the latter were free, it’s important to draw a line connecting Palestinian Arabs, Arabs who are Israeli citizens and Jews originating in Arab countries.

As in the words of poet Shlomi Hatuka of the Ars Poetica group: I still haven’t understood where the Mizrahim [Jews from North Africa and the Middle East] end and the Arabs begin.”…It is possible that the fates of the Arabs and the Mizrahim are more connected than the Mizrahim would like to admit, since they are all victims of “the White Ashkenazi-[Jews from northern and central Europe] democratic state.”

That’s why turning outward to the countries of the world to boycott us really is unpatriotic. Genuine patriotism would be in self-boycott—our boycott of ourselves. That does not mean boycotting the settlers, but each person boycotting himself. What is the value of our scientific achievements, our creativity, our academic research? What’s the point of the foods we’ll eat and how we will be joyous on our holidays if everything is tainted with the apartheid virus? Until we arise as a society and demand that the word “democracy” be imbued with new meaning, we will not be a free people in our own country.

“He who digs a trap falls into it.”

This is a movement for global justice, both political and economic. It focuses on the various levels of displacement, dispossession, and disinheritance that formed the active undergirding of globalizing capitalism as represented by apartheid South Africa, and today, apartheid Israel. This is not a “singling out” of one nation or one people; this is instead the focus on an offense against human rights and decency that becomes representative of all struggles worldwide for equality and dignity for all.

Background: Israeli Apartheid Week, 2010

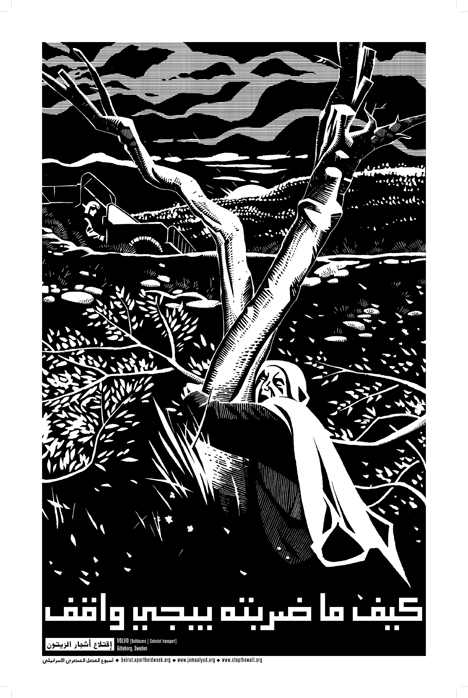

The posters that illustrate this article come from the events of Israeli Apartheid Week in 2010, which took place at the American University of Beirut. This “localization” was a bridging of international efforts to bring awareness to the plight of the Palestinian people from one of the nation-states which has suffered directly from Israeli aggression over the past decades.

In December, 2009, a few students got together at the American University of Beirut and started planning a week of conferences, workshops, interventions, and actions. This was based on the model offered by Israeli Apartheid Week, which had started six years earlier in Toronto; it was an effort to “bring home” and localize such efforts. A list of speakers was drawn up, performances planned, and with nothing much to offer except the basic idea itself, invitations went out.

The response was rather phenomenal, both in terms of support from the university itself, and the interest of international faculty/speakers to come to Beirut and engage with this issue within the Arab world. As their ideas became reality, the students were faced with the task of pulling together a multi-day event, organizing travel and accommodations, and logistically planning out as well as publicizing the events of the week.

“However beaten down, she stands back up.”

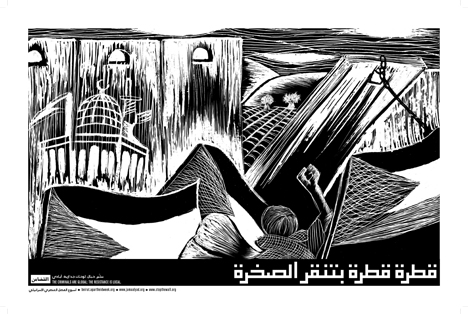

In collaboration with this endeavor, some students worked with me under the aegis of Jamaa Al-Yad (a Beiruti artists’ colletive) on a series of posters that sought to document the quotidian reality of apartheid Palestine, while simultaneously listing the corporations that economically profit from this occupation. Our idea was to combine these images with Lebanese proverbs to show solidarity with the Palestinian people via a common “spoken/visual language”, as well as to provide a means of disseminating the organization’s message and a schedule of events.

We presented sketches for the project’s posters to the editor of the local daily left-wing newspaper Al-Akhbar (at the time, Khaled Sayegh). Our original idea was to do a “plate swap” after the newspaper issue finished its print run, garnering a number of issues based on remaining paper and ink. Instead, the newspaper offered to print up the posters as a supplement to their Thursday, February 25 edition, which numbered roughly 10,000 copies.

Background: Jamaa Al-Yad

Jamaa Al-Yad (“hand come together”; or colloquially “fist”) is an artists’ collective based on the model of former collectives/groups such as the Taller de Grafica Popular (Mexico) and the Black Panthers (United States), their modern counterparts such as Dignidad Rebelde and Just Seeds, local and regional artists who have produced similar street works and activisms, as well as the rich poster tradition of the Levant.

From the collective’s bylaws is this description:

Objective: Jamaa al-Yad is a cultural association the aim of which is the research, implementation, dissemination, and reestablishment of various cultural manifestations including but not limited to craft, design, and art, by focusing on the local, vernacular, indigenous, and popular, using methodologies and means that ideologically reflect models of collaboration, co-operation, and communality, in the belief that such works and such actions are historically shown to, and continue to be likely to bring about beneficial social change and a betterment of the commonweal.

Our first project as a group was to produce a series of posters for the events of Israeli Apartheid Week, Beirut in 2010, the first time such an event was taking place in the Arab world.

Image

For our concept we were inspired by various artists whose approach to poster art focused heavily on social realism mixed with locally “read” symbolism, in media which might be considered both popular as well as populist. We also were informed by the aftermath of the 2006 July War on Lebanon in which actual press photos were denied as having been faked, or staged, or fabricated, such as those of the second Qana Massacre. We determined that the problem with press photography is that it is seen as “objective” and removed from those it describes; a super-mediation of content which a viewer can dismiss out of hand.

“Remember the wolf and prepare the cane.”

We decided to bring the “subjective” back, to take back control of the image by those whom it described; we see this as a particularly Lebanese response to a shared suffering from Israeli aggression, which we understand very well. We used actual press photographs as our basic reference material, and we expanded on this to highlight the economic and political aspects of the occupation, while nonetheless including symbols of hope in each image, reflecting the decades of patience, steadfastness, and resistance of the Palestinians.

Proverb

We combined each image with a Lebanese proverb in order to focus on the cultural and linguistic links to those suffering under occupation. We also wanted to literally “speak” of millennia of language usage which show the deep roots of understanding on this linguistic level. This common linguistic bond of the proverb is important to highlight, especially when contrasted with the erasure of Arabic as a language from Palestine itself. The oral here outweighs the written, in the sense that these proverbs are still an active aspect of the spoken Levantine dialect—to erase them would require erasing those saying them. To refer to them is thus to derive force from their very utterance.

Calligraphy

We used a basic form of square kufi calligraphy to further elucidate the craft basis of our work, using a form with deep linguistic, religious, and cultural roots. For technical reasons, it is also widely used in street graffiti; its form allows for easy creation of stencils. In terms of use, the fact that each proverb needed to be hand-crafted—you cannot truly make a static font of square calligraphy—rounded out our belief in the notion of craft, culture, and art as belonging to the people and as being a true expression of the people. Finally, the square kufi provided a strong and bold counterpart to the graphic quality of the images.

Audience

We decided to go with a poster format printed in newspaper form in order to keep cost low and to allow for wide distribution; we wanted to see the posters “activated” on the street by the readers themselves. For this reason we included on the first page of the newspaper a recipe for wheat paste as well as instructions on how to put the posters up. The newspaper further contained a manifesto as well as a description of the umbrella organization, and each poster provided links to the posters themselves, as well as web sites for further information on the events occurring at the AUB campus.

Language

Linguistically speaking, Lebanon currently suffers greatly from the colonizing imprint left over by the British and French mandates of the last century. Current graphic art practice, often funded by Gulf media agencies, and seen to be catering to this foreign outsider, almost requires that a “translation” take place in which 2 if not 3 languages compete for attention in the same graphic manifestation. Design decisions that seem rather innocent thus become political statements, determining notions of class, education, and other splintering aspects of Lebanese identity.

We made a decision to fight this in a very particular way. We did combine languages, but our tone/language used for the local population was very different than that used for the foreign/foreign-educated population. For example, we did not translate the proverbs, nor the articles. We translated the information concerning the predatory practices of companies profiting from apartheid, and the methods and means of such apartheid: fencing; homeland security; heavy machinery; etc. Thus the local population “reads” a poster that speaks of its suffering at the hand of foreign and colonizing entities; the foreign population “reads” a poster that points a finger directly at its economic and political system that continues to usurp and lay waste to the region.

“Drop by drop erodes the rock.”

Credits

There were many people involved in the project, which was communal in nature and thus hard to give credit for. We’ve also made a decision to not individually sign our work to preserve this collective nature. We worked hand in hand with the designers at Al-Akhbar newspaper to fine tune our work according to their design specifications. The editorial staff and pressmen of the newspaper also deserve much credit here and we again graciously thank them for their faith in this project as well as their support, labor, and supreme generosity.

Postmortem

We were not prepared for the success of the press run; in fact it almost succeeded too well. The newspaper sold out in particular neighborhoods, reflecting entrenched political “ghettoization” in the capital. At the same time, press outlets of politically “competing” parties/sects saw fit to reprint the posters in their pages. This was important for us as a nascent organization; that we not be “tagged” as being “of” any particular group, party, or political entity.

Outside of the refugee camps and our own efforts, we did not see many posters up. From what we understand, the goal of those purchasing the supplement seemed to be to hold on to the newspaper as a kind of souvenir. All the same, we did receive positive feedback from the generation previous to that which worked on the posters. They were reminded of their own efforts during the civil war, and finally opened up about such efforts with a generation for whom—in a gesture of protection—they had “traded in” such activism.

Later, during interventions on the Corniche on behalf of Palestinian cultural organizations where we handed out the newspapers, many people came up to us and told us how they had saved the poster issue. This meant the world to us. I remember at one point during our marathon working sessions, one of the members expressed the concern: “What if nobody puts them up?” I recall pausing, and replying that even if only one Palestinian child put up just one poster and found something positive in its message, and all of the others were destroyed, this would be more than enough. The posters in this collection to this day remain some of the most downloaded from our web site.

Links:

Al-Akhbar (Arabic): http://www.al-akhbar.com/

Al-Akhbar (English): http://english.al-akhbar.com/

Jamaa Al-Yad: http://www.jamaalyad.org/

Israeli Apartheid Week: http://apartheidweek.org/

Daniel Drennan is an illustrator and writer living and working in Beirut. He is founder of the artists’ collective “Jamaa Al-Yad”.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.