David Stairs

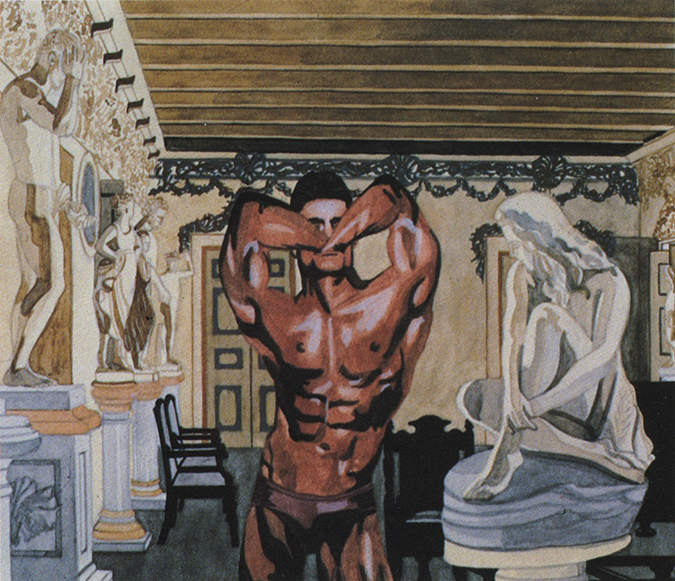

Control is the object of consolidation, what Nietsche once called the “will to power.”

Soul Searching

Consider the rise of multinational corporations. Monopoly is the capitalist ideal. Although shrouded in so-called antitrust laws preventing market domination— the idea being that competition is healthy for markets— captains of industry have always sought market dominance. For brief periods of time some capitalists, Henry Ford and John D. Rockefeller to name two, dominated their industries and became enormously wealthy.

Consolidation follows each and every industry from inception to domination to restructure and final collapse. As technologies change, industries come and go. Businesses, like Sears, achieve market dominance only to lose it to a later, more innovative competitor. Some corporations, like Standard Oil, morph into multinationals like Exxon, then merge with chief competitors, like Mobil. In this way numbers one and two remain at the top of the heap for a time.

The capitalist tendency toward consolidation long ago made the jump from heavy industry to service and software. Because of the ephemeral nature of the latter, it has become possible to not only grow out of all proportion, but to accumulate additional services at a frantic pace. Perhaps the classic example of this trend is Microsoft. Since becoming dominant during the 1980s as a result of its Windows licensing agreement with IBM, Microsoft has acquired upwards of 200 smaller companies. Some of these purchases, like 2016’s LinkedIn at $24 billion, exceed many of the business world’s previous large-scale mergers.

Not to be outdone, Google’s parent Alphabet has purchased nearly the same number of companies in 14 fewer years, since 2001, including Motorola and Youtube. And Yahoo! has acquired 114 companies since 1997. Not far behind are the cash flush behemoths Facebook and Adobe, both hellbent on controlling their little corner of the web. And let us not forget Jeff Bezos’ Amazon juggernaut, now entered into the movie production and distribution business.

Consolidation and merger are the order of the day in advertising, too. Agencies merge with other agencies, then are swallowed by large conglomerates. Ogilvy & Mather became part of WPP in 1989, while Chicago’s Foote, Cone & Belding was absorbed by the Interpublic Group, and merged with Draft Worldwide. J. Walter Thompson Worldwide, one of the globe’s largest agencies, with 10,000 employees in offices the world over, has been expanding since its founding in 1864.

This brings us to a curious recent instance of consolidation in something as abstruse as design writing: AIGAs’ collaboration with Design Observer. Design Observer— “writings on design and culture”— with its 800,000 Twitter followers, is now being presented by AIGA— “the professional organization for design”— with its 26,000 members. Design Observer had itself previously absorbed the architecture journal Places, and then Debbie Millman’s podcast Design Matters, so the AIGA deal seems a bit of a role reversal in a world where small fish usually get swallowed by bigger ones.

In the ongoing war for people’s minds, AIGA has the distinct advantage of utilizing faith as a recruitment tool. Just as with any major religion, reliance on the very human need for belonging drives recruitment initiatives at AIGA. And self-generated professional pride is the stuff of self-made professional legend in the design world. #Design Observer is touted as having been founded by Judith Helfand and Michael Beirut, and in the present design sphere it is perhaps natural that the surviving founders of DO, both AIGA Medal recipients, would want to lend, or should I say lease, credibility to their professional organization.

The problem as I see it is ultimately one of self-parody. Sheer size is seldom a sign of excellence, as one can see from many of the preceding examples, but criticality can have a lot to do with credibility. Writing at AIGA has always been shallow, more about cheer-leading for the profession than generating much in the way of criticism. And more recently, this might also be said for Design Observer. Gone are Rick Poyner’s incisive essays, or the efforts that characterized Julie Lasky’s Change Observer days. Although I appreciate the need for readability, DO’s current nod to the culturesphere follows a retreat from hard-hitting critique with an implied prefererence for inoffensive “observations.” But even observations imply a form of judgement, or connoissership, which would be a boon for AIGA. In a certain sense, the union with AIGA is probably a match made in heaven for two well-aligned entities, except I worry that, given DO’s reach and prior relevance, it might not be such a good omen for design criticism overall.

Then again, maybe consolidation’s the best thing that could happen here. While editorial influence of a perceived major critical brand could lend a sheen of legitimacy to an ambitious “professional” organization, a change in control of a major critical outlet, even if collaborative, exposes that outlet to scrutiny of a sort that would not occur otherwise. As Design Observer and the AIGA mix their design DNA, the quality of what they provide will take on the same look and flavor, opening the field to newer, fresher, and more challenging initiatives. I have no doubt such voices will arise, and look forward to their imminent arrival.

David Stairs is the founding editor of the Design-Altruism-Project