David Stairs

courtesy TheNation.com

The iconic images of Houston under 10 feet of water should have by now burned themselves into your brain. “How did we get to this point?” you ask. With one word: Design.

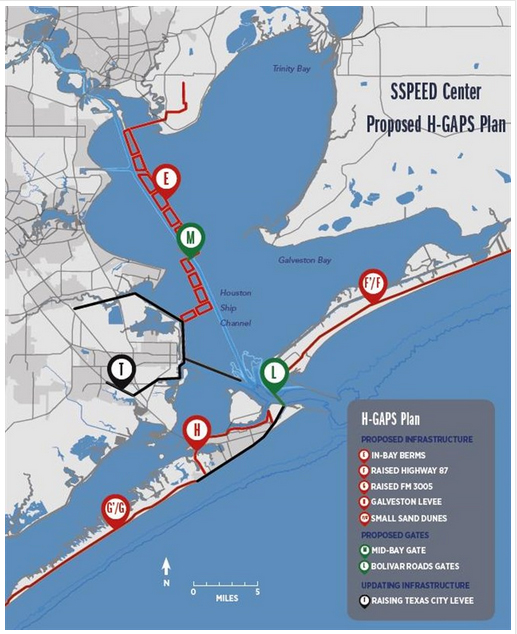

Plans have been underway to protect Houston and Galveston Bay from huge storm surges since at least 2008 when Hurricane Ike ravaged the area. Just prior to Ike a Rice University environmental engineer named Philip Bedient set up the Severe Storm Prediction Education and Evacuation from Disasters (SSPEED) Center. Working with academics from across the region, Bedient developed H-GAPS, the Houston-Galveston Area Protection System. H-GAPS was a collection of improvements that recommended raising roadways as evacuation routes, heightening the Texas City Levee surrounding Galveston and installing levees protecting the Houston Ship Channel, and building storm gates across the Bolivar Roads inlet to the bay. Trouble was, none of these ideas were ever implemented.

courtesy H-GAPS

Houston occupies a flat coastal prairie about 50 miles from the Gulf of Mexico. It has undergone massive growth over the last quarter century, reaching 2.2 million residents in the city proper, and upwards of 4.4 million when its surrounding county is included.

Houston is considered a developer-run city. Its citizens have rejected stringent building and zoning codes several times. Many homes in this flat city, only 80 feet above sea level, are constructed on a concrete slab. Local resident Sam Brody, quoted in the September 5th edition of the Chicago Tribune, stated, “Houston is the Wild West of development, so any mention of regulation creates a hostile reaction from people who see that as infringement on property rights and a deterrent to economic growth.”

courtesy politifact.com

When I say “design” is the problem, I mean several things. First off, developers happy to construct buildings they know meet sub-standard building codes in an area increasingly subject to serious flooding employ negative design, or design known in advance likely to fail. Secondly, officials in Harris County who have failed to enforce wetland mitigation regulations hid behind the apparent design of a solution to rapid expansion— an unenforced plan— knowing it was inadequate. Finally, since planning is the heart and soul of design, the planning around Houston which favored growth over everything else was the sort of failed design that emerges anytime avarice is in the driver’s seat.

Many periodicals are now quoting a Texas A&M report that reputedly states that from 1992 to 2010 30% of Harris County’s wetlands were filled or paved (Henry Grabar in Slate states it could actually be as high as 45%). And, according to the article I cite from Quartz, Houston developers not only don’t offset wetland destruction, but in over half of cases don’t even file completed permit paperwork.

Federally subsidized flood insurance allows nearly 10 million American households to exist in the 100-year flood plain. As a result of Donald Trump’s recent executive order rescinding Obama-era flood protection standards, Rob Moore, senior policy analyst for the National Resources Defense Council quoted in Quartz says, “What’s likely to happen is we’re going to spend tens of billions of dollars rebuilding Houston exactly like it is now, and then wait for the next one.”

Figures for relief and rebuilding in Houston run as high as 180 billion dollars. To allow people to continue to be nonchalant about risk while being callous about their surrounding environment is not only stupid, but is what I call a classic case of design and planning as problem rather than solution.

David Stairs is the founding editor of the Design-Altruism-Project