David Stairs

Completion of Kampala’s Northern Expressway has been plagued by delays in right-of-way acquisition

Returning to Uganda for the first time in ten years has held a few surprises. The charm of its people, and the beauty of Uganda’s countryside are unchanged, but the congestion in the capital Kampala is alarming. Partly this has to do with migration and growth. As the nation’s population increases, the sprawl of Kampala explodes.

When I first arrived in Uganda in September 2000 Kampala was a sleepy second-tier African capital of about ¾ million souls. Today that number has doubled, up nearly 30% since 2007. Many unskilled workers moving to a city like Kampala for its perceived “opportunities” are confronted with the harsh reality of un- or under-employment. I’ve written before about the surfeit of labor in African cities, and in Kampala at least that has not changed. Dump trucks are still loaded by shovel gangs, and the number of dead-end jobs in the city is expanding.

Near Kampala’s Owino Market, a vast redevelopment project in downtown Kampala, women in Airtel Mobile vests deliver plates of matoke and cassava to office workers. Swarms of motor scooters, “boda-bodas” in local parlance, clog the streets and endanger pedestrians attempting to cross the busy byways. People occupy hundreds of huts and kiosks selling cellphone airtime and m-pesa mobile money transfer services. In the vegetable stalls women sit on mats for hours tending small pyramids of tomatoes and oranges as men pushing enormous bikeloads of every imaginable good pass by.

Crowds of people at Kampala’s Owino Market

But as busy as city streets can be, it is the roads leading in to Kampala that are phenomenally clogged. These jams occur at every major intersection and roundabout and, at certain times of the day, can take hours to navigate. Unlicensed touts ply the gridlocked traffic hawking everything from chewing gum to oven cleaner, hoping to score a few shillings profit. This can’t be too lucrative; the current rate of exchange of Ugandan shillings to the US dollar is 3600:1.

Interest rates on private bank loans are running at 24%, and the central banks’ efforts to encourage improved rates by holding at 9.5% has not convinced commercial lenders to lower their rates. The resulting economic stagnation has all but killed manufacturing and drives high unemployment rates, especially among youths. This is creating a crisis for Yoweri Museveni’s 31-year reign. Members of his NRA Movement party have called for a “no” vote to constitutional efforts to extend political eligibility limits beyond age 75. This would force Museveni, now 72, to opt out of elections in 2021.

Whether he has the political capital to create a “president-for-life” situation in Uganda, as others like Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe attempted to do, remains unclear. Disenchantment with Museveni’s administration is widespread, and his efforts to blame Uganda’s problems on earlier despots Idi Amin and Milton Obote ring more and more hollow as his tenure in State House lengthens.

Meanwhile, major development projects, like the Entebbe-Kampala bypass and the Northern Expressway, lag way behind completion schedule as development partners like the EU fume about delays in acquiring right-of-ways and the disappearance of funds. African kleptocracy has been well-documented elsewhere in the political and development academic literature, and Uganda is no exception to the rule.

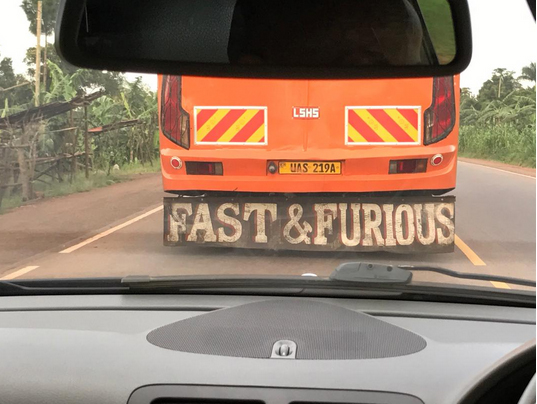

An overland bus in Uganda gives a false impression of normal traffic flow

The resulting gridlock: political, economic, and yes, automotive, will probably not budge until Uganda undergoes a regime change. Hopefully it won’t happen like Mobutu’s fall in Congo, which resulted in nearly twenty years of political upheaval.

Meanwhile, tens-of-thousands of taxi-vans belch diesel exhaust as hundreds of thousands of two-stroke mopeds burn oil, the exhaust clouds mixing with fine red dust to spell torment for pedestrians and doom for asthmatics. Ugandans seem unfazed. I’ve always marveled at the African ability to be patient with impossibly frustrating circumstances. That does not seem to have changed much. Call it faith in God, or fatalism– it’s definitely the only thing that keeps traffic moving under contemporary African driving conditions.

David Stairs is the founding editor of the Design-Altruism-Project