David Stairs

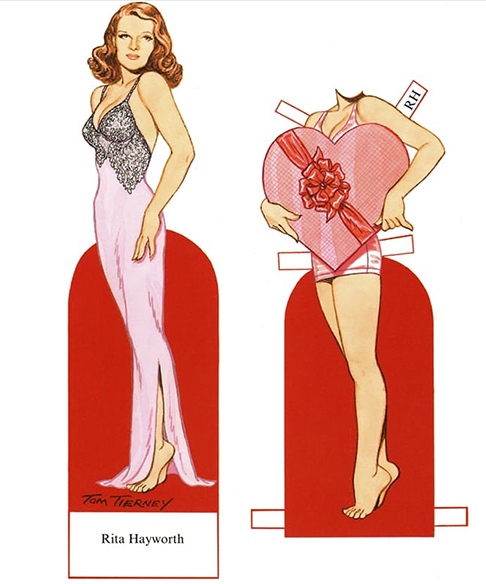

Tom Tierney’s Rita Hayworth paper doll published by Dover

As I sit by my Thermopane picture window reflecting on the wintry scene outdoors, I am distracted by the arrival of a mated pair of songbirds. A male cardinal hops onto my bird-feeder while his subtle mate shelters in a nearby bush.

In many species of nature males are strong, colorful, and dominant. The lion has his mane, the bull elephant his magnificent tusks, and my cardinal his outstandingly bright plumage. It is the means by which natural selection promotes the best genes while simultaneously protecting nurturing females by camouflaging them. Notably, among humans this is reversed.

Human males do not need to be either physical alphas or fashion plates to find a mate. And the burden of displaying color, flash, and sexual expression has been left to the females of our species. It is a multi-billion dollar industry called fashion.

Once upon a time human adornment was the domain of emperors and their courts. With the expansion of the middle class after the end of feudalism, couture was suddenly not only for courtiers. While most people still wore homespun, the expanding merchant class or bourgeoisie could suddenly afford to have someone else make their clothes.

This changed again after the onset on industrialization in the 18th century. As it became cheaper to weave large amounts of fabric, thanks to Jacquard’s programmable loom, a new industry of ready-to-wear, or prêt-à-porter in French, began to outfit exploding urban populations.

The modern fashion press can be dated to the founding of Vogue in New York in 1892. From the outset Vogue was published as a periodical specifically for the leisure class who, as documented by Thorstein Veblen, were conspicuously consuming during the Gilded Age. Conde Nast purchased Vogue in 1909 and expanded it overseas until today it encompasses 26 international editions.

Suffragettes of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were “liberated” for their time, but conservative in dress. They might no longer have been restrained by crinolines, but they still wore girdles, full-sleeve blouses, big hats, and long skirts.

By the end of the First World War, star designers like Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli, combined with the explosive popularity of cinema idols like Clara Bow and Mary Pickford, brought new emphasis to haute couture for the masses. Now we weren’t just talking about clothing and accessories, but also personal scents. But this is where things start to go awry.

The women who were the beneficiaries of the 19th Amendment, the so-called “flappers,” lived in a completely new world. New York, Paris, and Vienna of the inter-war years dramatically expanded the possibilities for women’s fashion. Babylon Berlin depicts the new world fashion order of Christopher Isherwood’s pre-Nazi German capital and the slender, louche, sometimes masculine styles of female dress then popular.

The ’30s and ’40s saw the expansion of cinema’s influence on fashion with actresses like Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo, and Myrna Loy setting the hi-tone for upwardly mobile women. The nearest one can come to a female equivalent of Chaplin’s Little Tramp would be a child star, like Shirley Temple. Full-grown girls were generally depicted as chic and well-dressed, an aspirational style for Depression-era women.

The 1950s were dominated by screen goddesses like Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor, and their look alikes such as Jayne Mansfield and Jane Russell. Wearing evening gowns and full-length gloves, the full-figured bombshell ideal offset a generation of stay-at-home Donna Reed-type post-war moms.

An exception to this rule would be the debutant-actress who married a prince, Grace Kelly. Her turn in To Catch a Thief with Cary Grant, filmed by Hitchcock on the Cote d’Azur, served as a sample of how the other half lived long before Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

The “gamine” look pioneered by Audrey Hepburn in the ’50s spilled over into the sexually liberated sixties, fueled by contraceptives and rebellion, marking yet another dramatic break with practicality. Carnaby Street’s “swinging” styles, promoted by supermodels like Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton, and popular bands like the Beatles and Rolling Stones, introduced a generation to influences ranging from drug culture to Indian style. When the decade ended in the paroxysm of anti-Vietnam war protests, the stage was set for a retreat to the back-to-the-earth values and style of the flower power generation.

This boom and bust cycle of fashion is only one of the industry’s hallmarks. Lifestyle promotion has been a commonplace of consumer culture for 130 years. But the emphasis on fashion, now so prevalent that most young women are socialized to feel uncomfortable about leaving home in the morning without wearing makeup, has long since surpassed the point of desire. The addition of eating disorders to the canon of psychological illnesses, as girls purge in an effort to emulate their favorite model or pop star, is indicative of the anti-natural emphasis our society places on female appearance.

The fashion industry is also obsessive about change. Planned obsolescence, criticized in industrial design as mere styling, is a fact of life in fashion. Perhaps this is because fashion design, of all the design professions, deals with the most ephemeral end product, the one most susceptible to the whims of social hysteria and economic opportunism. Yet, the industry hails and even celebrates the ephemeral.

Is this constant change and style updating sustainable? It’s a question people in the industry sometimes ask themselves. Perhaps a better one might be “Why fashion at all?” But this can be easily rebutted by the amount of income constant shifts in outward appearance generate. The $2 trillion value of worldwide fashion retail could easily float the GDP of several developing world nations. The sheer number of humans involved in the production and distribution of fashion, from the cotton farmers of Egypt to the sweat-shop seamstresses of Bangeladesh, or the cow herders and leather tanners of India to the retail mall employees and personal stylists of Singapore speak to this. No doubt about it, money talks.

Returning to my original premise, that fashion is unnatural— can there be a counterargument? The industry’s promoters and apologists will obviously disagree with me, arguing that clothing has been part of society since Adam and Eve left The Garden. Obviously, I will never suggest that there is not a need for protection from the natural elements. Most creatures come co-evolved for their living environment, which is why there are polar bears at the arctic, but not giraffes. Human beings are the exception to this, having populated all locations and climates of the globe. And it stands to reason that part of the technology that has made this possible is clothing.

And yet, a better example than the tremendous gap between necessary body coverings and red carpet evening gowns cannot be found. One would be hard pressed to argue that the latter is an environmental necessity, rather than a deranged social obsession developed by a misguided species that has long since forgotten how to tell the forest or its trees. Or put another way, to understand the difference between surface and substance in fashion, one need not look very deep. Any potential relation between trend and survival is strictly a la mode.

David Stairs is the founding editor of the Design-Altruism-Project.