David Stairs:

I had an inauspicious beginning as a painter.

When I was 10 or 11 years old, I received a paint-by-numbers kit. I set about dutifully filling in the pre-designated spaces with the provided colors, used directly from the bottle— no color mixing— and when I was finished I had something that approximated a bird. An eagle landing, to be exact.

When I look at my first masterpiece now, I readily understand why I did not become a painter. It really sucks. Following the provided color palette resulted in a dull, muddy picture. What’s worse, my brush handling skills were so poor, I could not even stay within the lines. It’s a blobby, mushy mess. Worst of all, it’s terminally unoriginal, some corporate hack’s notion of a nature scene, since about 1810 the lowest concept in Art.

I teach an introductory course in Contemporary Art. The whole point of the course is to instill aspiring student artists not only with a sense of what is original, but with the ability to recognize originality when they see it. There is really nothing more significant to success as an artist. Since at least the time of the Dadaists, or about 1918, this has meant the work must be provocative. As early as the 1850s Gustave Flaubert was on a mission to provoke the bourgeoisie of his era. The realism of Courbet was then giving way to the often outrageous ideas of Manet, whose nudes shocked the Parisian audiences of the 1860s.

Over here in America, Currier & Ives were milking the popular appetite for pastoral Americana with their winter scenes and prints of Mississippi riverboats and nighttime trains. While in France experiment was being driven by the Impressionists, Americans were still exercising their love of nostalgia as Currier & Ives continued production right through until 1907. It’s amazing that this love of corn-pone landscape survived up to the present day, but in America it finished the 20th century with a bang. The works of Hallmark artist Thomas Kinkade, and television art teacher Bob Ross have survived the demise of both artists, becoming collectible for some.

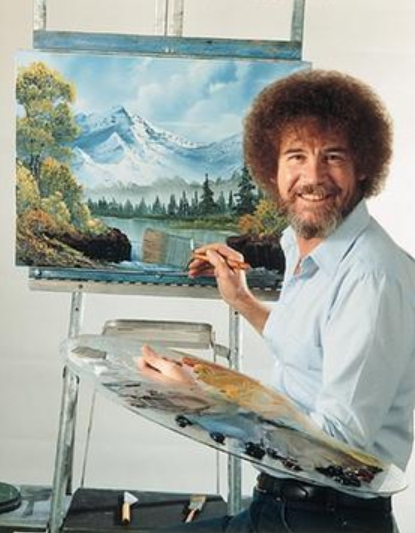

Bob Ross publicity photo

Ross, who claimed to have completed more than 30,000 works, learned to paint while stationed with the Air Force in Alaska. He mastered a “wet-on-wet” technique using oils, as had Hals, Velasquez, and Caravaggio, to name but a few famous predecessors. His television program, The Joy of Painting, ran from 1983 to 1994, and to this day through reruns. Ross painted the same scenes of mountains, trees, and clouds over and over again, pumping out feel-good pabulum to the very end. His company, Bob Ross, Inc. still markets art supplies, videos, and how-to books. Ross died at age 52 of lymphoma, in 1995.

Kinkade, the self-designated “Painter of Light,” studied at UC Berkeley and Art Center College in Pasadena. After working as a background painter for animator Ralph Bakshi, Kinkade launched a career as a painter of bucolic and idyllic scenes, things such as lighthouses, gardens, and stone cottages. Like Ross, these images were usually devoid of people. Kinkade

parlayed his paintings into a multi-million dollar business of printed, hand-retouched reproductions of these scenes, marketed both online and through a series of franchised galleries. He died in 2012 at age 54 of an alcohol and valium overdose.

Central Park in the Fall. 2010. Thomas Kinkade

Referencing these artists to the 19th century Hudson River School feels overly generous. For one thing, those earlier painters did not have Modernism in their rear view mirror. For another, both Ross and Kinkade were obsessively focused on quantity over originality. Nothing could be less representative of Art in the contemporary world. Many contemporary artists produce volumes of work. Jeff Koons employs 100 studio assistants; Andy Warhol called his studio The Factory and made a business of painting portraits and pets. But these artists did not fall back upon the clichés of yesteryear, and any such references to formula are always made with a wink and a nod. This is what distinguishes Koons and Warhol from Ross and Kinkade. Not only does their work resist genre, the latter’s meat and potatoes, but they do not take themselves too seriously.

I need to say that it is not a crime to be popular as an artist. Picasso pursued many popularizing art forms in his later career, including prints and ceramics. These media, which generate multiples, make them more affordable to a broader audience. But the hubris of Kinkade’s contention that his work was in every 20th home in America is one of the things that cause critics to relegate it to the realm of kitsch. That, and just trying to out Currier Currier. Art can be many things, but as a contemporary reflection of human endeavor, it long ago ceased being about making people feel good.

David Stairs is the founding editor of the Design-Altruism-Project.