An irresistible object, a homeless man and the future economy of the world

Tasos Calantzis

On a chilly late autumn afternoon the curator of one of Europe’s most prestigious art and design museums clicked through images of a new wooden vase and immediately ordered 8 pieces via e-mail for sale in the museum store. She hadn’t seen the actual product yet but liked the pictures enough to place the order.

Two weeks earlier, the creative director of one of the largest safari lodge companies in the world, which owns some of the most prestigious properties on 3 continents, stopped while going through images of items for new décor in the lodges. “He’s not the kind to get excited about a new item typically, he’s seen so much over the years, he just kind of goes ‘yes’ or ‘no’ but this time he stopped and said “Wow; we’ve got to have those”, says an assistant.

Just over a month earlier, two buyers from one of America’s most respected chain of décor retailers had an unexpected meeting. They were on their annual global pilgrimage to source the most interesting items from around the world to stock in their stores. “This is unique; we’ve just come from the Milan furniture fair and there’s nothing at all like this available”, said one of them, studying the bowl in his hands.

The man who had made the items that so captivated these people couldn’t have known less about how his work was affecting them. His name is William Maseng and he lives in a squatter camp incongruously wedged between one of Africa’s most impressive church campuses and one of its most upmarket shopping malls. The village has been neatly laid out by a local charity with a grid of wide dusty streets, dotted with a few above ground water tanks. Its 800 houses are mostly made from tree branches wrapped with thick plastic film salvaged from building sites and billboards.

William Maseng

William’s own house used to be an ANC election billboard and fragments of its message overlap at comically XXL size. Outside his front door, William has placed a salvaged wooden table where he does his work assembling slivers of wood into the decorative bowls, vases and lampshades that made such an impression on those décor experts in Europe, South Africa and the USA.

William is not a craftsman, he’s a construction laborer. He arrived in Pretoria in 1981 from Kuruman, a pretty town of 12,000 inhabitants on the edge of the Kalahari Desert several hundred miles away. Faced with few opportunities for work, he did what hundreds of thousands of South Africans do every year and moved to the city to look for a job. Nearly three decades of part-time work and countless hard knocks had left him homeless, penniless and out of luck. He found himself living in the long grass and dense bushes in a green belt lining the wealthy end of Pretoria, together with several hundred people with similar stories, all of them virtually invisible to their neighbors whizzing by a few hundred yards away in their cars.

Shacks where William lives

In many ways, William’s story represents the heartache and hopelessness of almost half of South Africa’s people. While half the population attend good schools, earn a trade or graduate from university and go on to comfortable middle class lives, the other half is stuck on the wrong side of a growing income gap. For every story of promise and hope, often because of angelic NGOs like Tswelopele which formalized William’s village, plucking it’s now residents from the urban veld to give them a better chance, there is a story of incompetence and failure such as the 27,000 dysfunctional schools in the country, still paralyzed after 14 years of democratic freedom.

The bowls that William assembles started life as a short conversation with Professor Neil Gershenfeld under the cavernous glass and steel of Cape Town’s slick new Convention Centre during the 2007 Design Indaba conference. Professor Gershenfeld runs the Centre for Bits and Atoms at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. A bearded man with a bush of graying black hair, Neil is a constant blaze of energy and intelligence, attributes that contributed to his being named one of the Prospect/FP top 100 public intellectuals in the world.

He has a vision of the future. He believes that our world needn’t have huge factories making millions of widgets which are transported around the world in huge ships and into warehouses and trucks that all spew out smoke and carbon. Prof. Gershenfeld says that this almighty expense to deliver a single widget to the store shelf on the day that we choose to buy is composed mostly of wasted energy. He says in his book, FAB, and in his popular talk on www.ted.com that instead of transporting tons of matter around the world we should simply transport the information because that travels around the world in a millisecond and at almost no cost.

This vision is encapsulated in the term personal fabricator, which Neil uses to describe the future invention that will make this all possible. You or I will sit at home, order a product online and a cabinet-sized machine in the basement will make it for us before our eyes. This technology is at the mainframe stage of development according to Prof. Gershenfeld and just as some people once said that there was no use for a personal computer, it may be hard to believe that we will one day each own a personal fabricator.

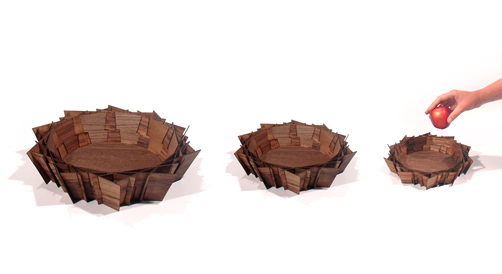

Readymade is developing a brandline of products called Nest.

To prototype the idea, Prof. Gershefeld has created over 60 fabrication laboratories around the world, including in South Africa. These Fab Labs are crude versions of the personal fabricator consisting of a room full of laser cutters, micro milling machines, plasma cutters and so on. Any person can walk in off the street, learn a little CAD software and start making things.

What Prof. Gershenfeld has been looking for is a way to commercialize the work of the Fab Labs so that the prototyping of his vision of the future can go beyond technical feasibility and into the commercial realm. That prompted the team at Readymade, an industrial design company, to design products that could be made in any Fab Lab and sold around the world. If successful, a good candidate would be able to be made at the Fab Lab closest to the customer that ordered it.

The peculiarity of this task wasn’t lost on Readymade whose daily work consists mostly of designing technological gadgets for large multinationals like Motorola, Philips and Mitsubishi; things like digital pocket radios, mobile phone headsets and remote controls. Despite not being known for creating decorative home wares on a pro bono basis, the PR allure of working with MIT and the chance to burnish the artistic side of the portfolio held sway.

The first result is the decorative wooden bowl made by William Maseng that so captivated the experts on three continents. It is constructed from laser cut pieces of wood which are interlaced to create the impression of a bird’s nest. When holding the product, one is aware of several apparent contradictions: it is complex for something with such a simple function, it is striking, beautiful even but by no means pretty, it is delicate but at the same time rough, and it is organically random but also precisely ordered.

These contrasts are perhaps explained by Readymade’s unusual situation as an African company designing techno-gadgets for first world corporations which are sold around the world. They are also possibly explained by the bowl’s attempt to answer the question of what it means to be a 21st century African.

For William Maseng it (at least partially) means earning some money making bowls, which if they become popular, could mean his first regular income for a long time. For others, the Fab Labs in South Africa provide the chance to experiment and make with greater dexterity than before. For Readymade it could be bridging the gulf between thinking global and acting local when you’re sitting at the far end of Africa.

The idea of employing homeless job seekers like William to assemble the bowls was serendipitous rather than planned, but has allowed very careful assembly of a delicate product in a way that mass production cannot reproduce.

The combination of living close to the elements and having plenty of time can be life-threatening for people like William. In another context, in a busy world momentarily sick of artificial excess, touching the elements and having enough time are warm, real and luxurious. Maybe some of that warmth is captured in the bowls that William makes.

Anya Calantzis and William Maseng (with Hannah Calantzis)

It’s probable that the nest bowl will not create the new world economy and that it may not even dent South Africa’s towering unemployment. If homeless South Africans make the bowls, they will still be shipped around the world creating carbon dioxide; they currently consist of American Walnut that has already made one very long trip. It is possible that the nest bowl represents little about beauty, warmth, reality or commercial sense. Nonetheless, there is still something beautiful about an idea that by its very existence allows wealthy connoisseurs of design across the world to choose a bowl made by a man sitting outside a shack in South Africa and to pay him for the privilege.

Tasos Calantzis and his wife Anya are the motive force behind Terrestrial, Africa’s first red dot winner and a 2009 INDEX award finalist. They live in Guateng, South Africa.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.