An Xiao Mina

In "The Texting Culture of the Philippines," a recent article for Design Observer, I explored some of the design strategies centered around mobile phone culture in the Philippines. It’s a well-known fact to anyone who’s visited the country–with upwards of 600 text messages per month per user in 2010, the Philippines is the world leader in mobile messaging. The second, the United States, comes in at a comparatively paltry 420 messages per user in the same time period.

It’s hard to overestimate just how pervasive the mobile phone is in Philippine culture, so much so that it’s embedded into daily life. To expand a bit more on that article, I thought I would share a few more photos of some of the design strategies that have evolved around this culture.

I was amazed to come across this cell phone charger and caller in a convenience store in Manila, but my Filipino friends didn’t seem too impressed. It had already become part of the fabric. What you see on top are two cell phones, tied to the two most popular networks (Smart and Globe). You pay per minute of usage, meaning you can either send a text message or call. By choosing the network phone you use, you can maximize your minutes by taking advantage of in-network discounts. At bottom, you’ll find secure cell phone chargers, with a variety of plugs for the many different phones people might use.

Shortly after a massive storm hit the south and flooded the cities, requests for donations came in through social media. This was already familiar to me, as I tried to help remotely with relief efforts for 2009’s how quickly these @philredcross relief tweets appeared on Twitter. This time, I was in the country and was able to try a donation. It was surprisingly simple – I texted, and the money was transferred directly from my phone credit. A similar process can be done for any money transfer, including person to person, up to a certain amount.

Mobile culture extends to wifi culture. While wifi can be found in almost every cafe in Manila, it’s not always a given, and sometimes connections speeds can be slow. USB modems are a popular alternative, but so are pocket wifi hubs, which a friend of mine carries with her everywhere. Not only does the wifi plan allow you to create a network for yourself and your computer or smartphone, it allows you to share that network with a select group of friends nearby. In so doing, it creates a shared experience among friends and coworkers, much like splitting earbuds or having a group dinner.

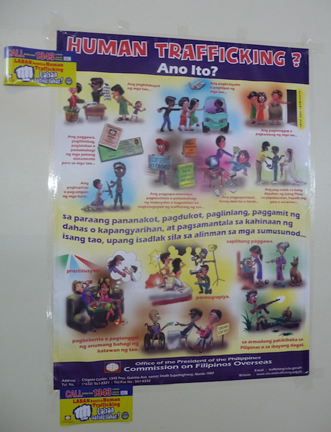

This poster in Tagalog explains the warning signs of human trafficking and what to do if you spot a possible trafficker. What’s interesting to me is the addenda–the stickers that provide a phone number for action. They stand out from the poster itself, thus highlighting their presence, but I also wonder if they’re relatively new–human trafficking isn’t a new problem, but the possibility of using one’s phone to identify or report a trafficker is a new potential solution.

This kiosk outside a McDonald’s in the Manila area. For a quick top-up of your phone balance (PHP 50, or about USD 1), users can get a free drink or burger ("Burger Mcdo" is the local name of a burger at McDonald’s). Partnerships and promotions like this suggest competition between phone networks in what is clearly a lucrative market.

This is a familiar sign in the Western world, but I liked that I came across it in two languages while visiting a Buddhist temple in Manila. There are two rituals now before entering the temple space: take off your shoes and turn off or silence your phone.

So pervasive are ads for texting bonuses and benefits that they are repurposed and used in other contexts, such as to decorate this covered bridge outside Manila. Sometimes it’s an informal repurposing, as depicted here, and sometimes it’s the company distributing their own. I didn’t get a chance to delve into the cause and effect, but I have a feeling the companies were responding to informal usage. Advertising, after all, is advertising.

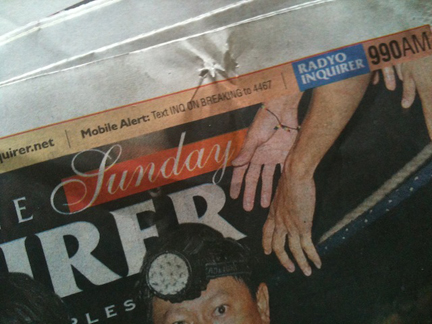

In both print and television media, Filipinos can sign up for text message alerts about breaking news. Text messages have become part of the larger media fabric, which includes print, radio, television, social media and others. Most if not all the media outlets I encountered had some kind of text messaging service, whether just to deliver news or also to solicit feedback from the audience.

At first glance, it can seem like mobile phone culture is strongest amidst the lower classes. As in most developing countries, the mobile phone is the only communications device for many people, serving as their internet, phone and computer all in one. But texting culture extends to everyone, including those who want to sign up for a credit card. In the US, I might expect a web site and in Korea, I might expect a QR code. But in the Philippines, it’s a phone number to send a text message to (along with a cute pun).

These are just a few examples. Indeed, every day was a surprise for me as I learned more and more about mobile phone culture. I learned about texting slang, probably a dialect in itself. It’s unintelligible not just to foreigners but even to native speakers of the relevant dialect (and the Philippines has many many dialects). A basketball team named after the Talk ‘N Text Phone Pals brand. The practice of randomly texting numbers in the hopes of finding a new friend to chat with (like Chat Roulette, but without the X rating). Prayers forwarded to me during times of crisis or holy days.

I’d love to hear more examples from readers – there’s a treasure trove of digital culture that’s little understood outside the Philippines, and during my short time there, I only got a brief glimpse of the tip of the tip of the iceberg.

An Xiao Mina is an American designer, strategist, and researcher who recently worked on the Gwangju Design Biennale’s Un-Named Design exhibition. She focuses on the role of social media and communications technologies in building communities and empowering individuals. Find her on Twitter here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.