Philip Borkowski

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of published Masters theses that started last year with Jesse McClain’s Actively. Many thanks to Wes Janz for making it possible.

image: Wes Janz

Never before has human creation effected the world as much as it does today. While living next to a large construction site, I started to observe the frequency with which a 40-yard dumpster was being filled with what many people may consider waste. Here in the United States, we live in a throw-away society, but it has not always been this way nor is it this way in many other societies. “Up until the nineteenth century, recycling architectural elements from old buildings was normal all over the world. In other places around the world it is an integral part of their society.” (Bahamo?n 84) Today, extreme recycling still takes place in developing countries, not as an environmentally conscious decision, but as a way of life. We can learn from these developing countries.

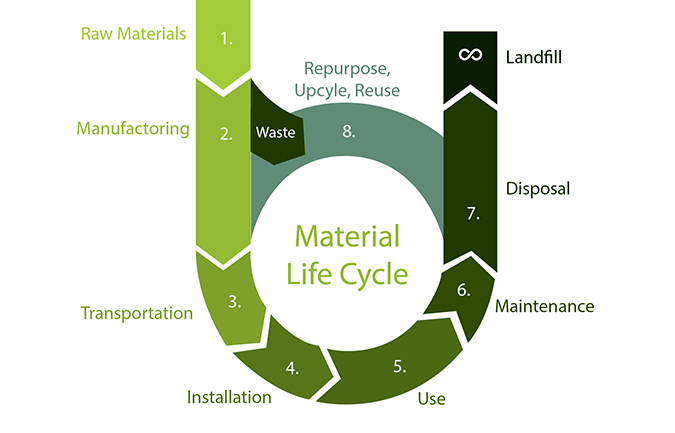

As a young architect in design school, I see issues of reuse being preached but not practiced. Many architecture firms claim to be on the cutting edge of sustainable design, yet they make no effort to reuse materials. Why does this happen? What are alternatives for discarded products within architecture? As architects and designers, what can we do to get the most out of these underutilized materials? This project tells the story of transformation. It challenges the traditional method of material life cycle, and explores the alternative design possibilities of a seemingly outdated material through a nontraditional circular way of thinking and making. Waste today is seen as dirty, undignified, and useless, and is almost always kept out of sight. Those who work with these unwanted materials in the first stage of collecting waste are seen as people who belong to the lower social level. In developed countries such as the United States, we have created a system in which we generate tons and tons of solid waste that is either burned or buried every day. “As Americans we represent 5% of the world’s population and produce 30% of the world’s trash” (RCU, 2015). Only a very small percentage of this waste is being recycled, even though there are some serious environmental consequences that go along with this. How are we as citizens and people going to solve this environmental problem if we keep the waste that we are creating hidden and out of sight?

I see these abandoned materials as a challenge. Many large objects, like furniture, pallets, and construction materials are still perfectly useful after they have been thrown out or replaced by newer models. Other materials may no longer be needed for their original purpose and could serve another purpose with little or no need for interference. Dumpsters, curbsides, landfills, etc. are full of useable resources, so it seems silly to me to go out and buy something that we could potentially use for free.

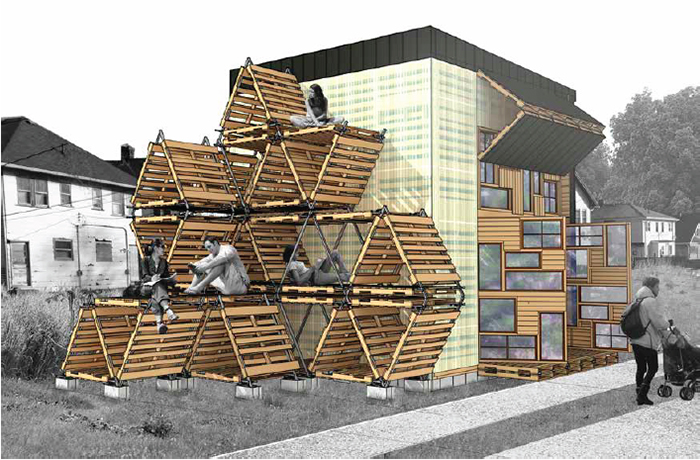

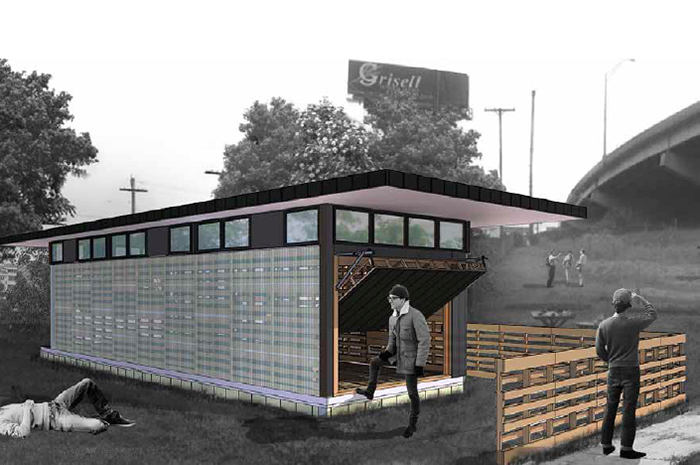

I would rather solve problems than create new ones. By taking a look at the problems at hand and turning them upside down, I hope to be able to create something unique and beautiful. In a world where raw materials are becoming more and more scarce, creating architecture out of found or unwanted items is a matter of common sense. This project proposes the design and component development of a small dwelling which challenges conventional construction methods and orthodox ways of collecting building materials. The following precedents will begin to explore the type of action proposed. It is not a solution to our societal problems surrounding garbage, but it is a call to us as citizens and architects to start to see the value in everyday items that most may consider trash. It is a way to stimulate the architectural practice, asking for more engagement and a philosophy beyond working with new products by looking at new ways of using old products.

Furniture Waste

While exploring dumpsters and curbsides, I noticed that much of the durable waste that I was observing was furniture waste. To further explore what others were doing with discarded furniture items, I decided to visit a local furniture store. Gilberg Furniture is a small family owned business located in New Bremen, Ohio. The store has been in business since 1926. It employs roughly eight people, including 3 delivery persons, and 5 sales staff. The furniture store sells and distributes furniture to residents primarily within a 30 mile radius of the store. The store not only delivers new furniture, but also accepts old, worn-out, or outdated furniture. It is a common everyday occurrence for this furniture store to receive old furniture for disposal. They have been collecting and disposing of furniture since they opened their doors in 1926. They dispose of many different furniture materials such as bed frames, box springs, mattresses, couches, recliners, entertainment centers, pallets, etc. The old unwanted furniture is collected and stored in the rear of the furniture store. Each month the unwanted furniture pieces are loaded into a large dumpster. The dumpster is then taken to the landfill without any sort of recycling or salvaging of material.

I was able to talk to the manager about some of my concerns with the discard of seemingly useful materials. I asked him if there was any way in which they prevent this material from ending up in the landfill. He explained that they do try to salvage or reuse materials where they can, but there is no profit to be made. He explained that some of the furniture that they pick up is donated to Goodwill when it is in good shape, but even Goodwill will not take everything. It is normal protocol for furniture stores to dispose of materials in this manner. This visit really made me think about how our society’s model is often “out with the old and in with the new”. Although many people would see these items as trash, I had started to see these items as potential building materials. In the short time that I was there I began experimenting by taking some of the items and placing them in ways that began to create a shelter.

Construction and Demolition Waste

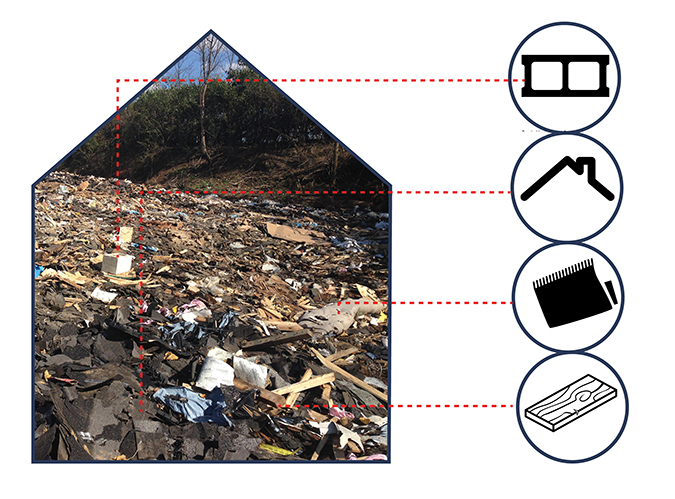

Xenia Demolition Landfill is a small family owned business located in Xenia, Ohio. They employ roughly seven people and it is just one of forty five EPA Licensed Construction and Demolition landfills in the state of Ohio. Currently the landfill sits on fifty acres just outside the Xenia city limits. The landfill accepts almost any of the materials that go into the building process including bricks, siding, wood, metal, insulation, etc.

The business did not originally start out as a construction and demolition landfill. Their primary business was selling sand and gravel. It was not until 1991 that they began accepting construction and demolition debris. The land was ideal for the dumping of unwanted building materials because there was already a large void where gravel and stone had previously been excavated. This created a way for the trash to be easily buried and kept out of sight. The city of Xenia owns the land where the construction and demolition materials are being dumped. Although Xenia Construction and Demolition owns the business, they have to give 7.3% of their profits to the city of Xenia for the use of the land. 75% of what this landfill receives is asphalt shingles.

This visit opened my eyes to how wasteful our society really is. In this case it surely is “out of sight, out of mind.” In the hour that I was able to observe the landfill, seven fully loaded trucks dumped their contents into this large man made hole in the earth. I witnessed numerous salvageable building components being dumped, compacted, and buried within minutes, without anyone considering the reusable potential of what they were putting in the ground. Turn of the century bricks and heavy timber, large shipping pallets made of 2×4’s and 4×4’s, and mounds of asphalt shingles are just some of the many reusable items that I witnessed being discarded. Surely, there are alternative uses for some of the items being discarded. Why are we not utilizing these materials to their fullest potential? As I talked to the manager about my concerns, he told me that there is no profit for him to salvage anything. He explained that he would like to break up the concrete and asphalt that comes in, but it is currently easier and cheaper to bury the materials.

Making

image: Wes Janz

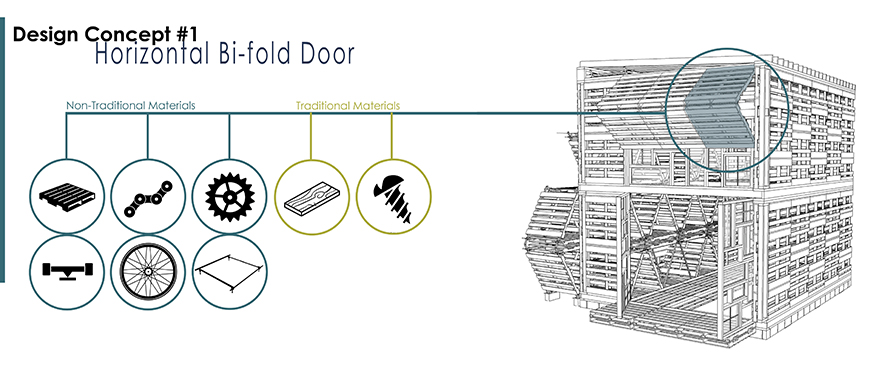

A horizontal bi-fold pallet door, and a mattress foundation overhead door were designed as an architectural response to my research endeavor. The installations were constructed in order to contribute to the larger conversation about reuse. The choice to explore movable components came from the possible application in small residences or alley flats. The movable mechanical parts allow the user to be involved and observe the salvaged materials working.

The pieces promote the reuse of materials, while providing practical knowledge about secondary uses for many commonly found waste materials. The installations create a unique and non-traditional functional work of art. They were built using primarily salvaged materials and under the labor of primarily one person.

Location and availability played a key role in what I used for this project. I wanted to focus on a sustainable way of building. This included looking for materials that were being discarded abundantly or had already been through their traditional material life cycle. I also wanted materials that could be easily obtained locally, in order to cut down on energy used in transportation. My architecture background played a key role in helping me make my design decisions. Within architecture school I have seen similar concept designs, but I have never seen any of these designs being built. This type of design could be implemented in small homes for low income families, young professionals, or do-it-yourselfers.

Overall, the cost of this project was low considering the cost to make these prototypes from all new items. All the reclaimed or salvaged materials were considered waste before I obtained them and were free to me. The dimensional lumber and the hardware came to a cost of roughly $40 for each prototype. The materials that I used were all available to me within my community. By providing a nontraditional and economical way of thinking, and designing using unwanted items, I hope others start to take on similar tasks. With more prototypes, I could see this product becoming a standard part of residential building.

References

Statistics: Elizabeth O’Brien, Bradley Guy, Angela Stephenson Lindner, (2006) Life Cycle Analysis of the Deconstruction of Military Barracks: Ft. McClellan, Anniston, AL. Journal of Green Building: Fall 2006, Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 166-183. EPA. “2009 Facts and Figures.” MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE IN THE UNITED STATES. 1 Dec. 2010. Web. 30 Apr. 2015. Joanna. “EPA Reports 9.8 Million Tons Per Year in Furniture Waste.” PlanetSave. 4 May 2011. Web. 30 Apr. 2015. NAHB. “Construction Statistics: New Housing Starts Forecast, Construction Spending Statistics.” Construction Statistics: New Housing Starts Forecast, Construction Spending Statistics. 2001. Web. 29 Apr. 2015. Scrap House. “ScrapHouse – Statistics.” ScrapHouse Statistics Comments. 2005. Web. 29 Apr. 2015. Sandler, Ken. “Basic Information.” EPA. Environmental Protection Agency, 2012. Web. 29 Apr. 2015. Recycling Coalition of Utah. “How Much Do Americans Throw Away?” Recycling Coalition of Utah. 2015. Web. 30 Apr. 2015.

Abstract/Literature Review/Precedent Studies:

Addis, William. Building with reclaimed components and materials a design handbook for reuse and recycling. London: Earthscan, 2006. Print. Bahamo?n, Alejandro, and Maria Camila Sanjine?s. Rematerial: from waste to architecture. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010. Print. Baraka:. Dir. Mark Magidson. Perf. Ron Fricke. The Samuel Goldwyn Company, 1992. DVD. Berger, Alan. Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban America. New York: Princeton Architectural, 2006. Print. Broadstreet, Jim. Building with junk and other good stuff: a guide to home building and remodeling using recycled materials. Port Townsend, Wash.: Loompanics Unlimited, 1990. Print. Chandrashekhar, Shekhar. Research in Materials and Manufacturing for Extreme Affordability: A National Science Foundation Workshop, Ball State University, Department of Architecture, Muncie, IN, USA, March 18-19, 2011. Muncie, Ind.: Department of Architecture, Ball State U, 2012. Print. Cruz, Teddy. “How Architectural Innovations Migrate across Borders.”Teddy Cruz:. 1 June 2013. Web. 1 Dec. 2014.

Philip Borkowski is a 2015 M.Arch graduate of the School of Architecture at Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.