David Stairs

In the Land of Celebrity, the Expert is King.

It would be difficult to argue that our society is not obsessed with celebrities. From film stars to athletes, politicians to the Pope— and let’s not forget the British Royal Family— in America the Cult of Personality reigns supreme. Even small-fry celebrities, like reality TV stars and Instagram influencers garner more than their share of adulation. And every one of them is considered an “expert.”

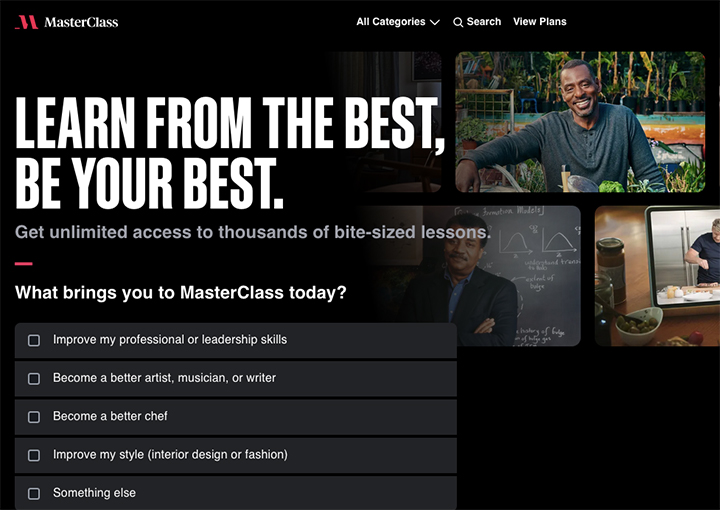

What do Helen Mirren, Howard Schulz, Wayne Gretzky, and Malala Yousefzai have in common, other than their celebrity status? They are all lecturers on the MasterClass website. Want to know more about cooking? Why bother with Julia Child or Marion Rombauer when you can listen to Alice Waters and Wolfgang Puck? Need some pointers about film making? Save that tuition money from film school because you can now learn from Werner Herzog, Ron Howard, Ken Burns, and Martin Scorsese in the comfort of your own livingroom.

Whether in sport (Stephen Curry and Serena Williams), Music (John Legend and Christina Aguilera), Design (David Carson and Frank Gehry), Acting (Natalie Portman and Samuel L. Jackson), or business (Kris Jenner and Richard Branson), for $10 per month the MasterClass stable of superstars has you covered. Not that any of there people need any additional attention, given that so many of them have spent a good portion of their adult lives self-promoting. But that’s not the point, is it?

In 180 classes across eleven categories, MasterClass pretends that the best way to learn is to pay to listen to a celebrity. It does not matter that the best teachers in the world are unsung, women like my son’s Ugandan third grade teacher Ms. Rose, who was a genius of compassion and understanding. Unfortunately, expertise is one of the things academia misapplies. Universities desperate to use their faculty’s notoriety as a recruiting tool ask professors to 1) list their areas of expertise and 2) state whether they would be available to speak to the media on their topics of strength. Even at my mid-major mid-western mid-size institution, I have seen faculty colleagues interviewed as talking heads on the evening PBS NewsHour. As the location of a Public Broadcasting affiliate, I suppose such things are inevitable.

Of course, in design, especially Graphic Design, there are many more online tutors than just David Carson. Every aspect of the trade from posters and books, to web design and motion, and especially to logo design, is covered in minute detail. This is the natural outgrowth of universal digital literacy, where everyone wants to have an online presence and brand his or her own small business concept. Again, this has much less to do with expertise than skill training and, as with make-up tutorials, everyone wants to be good at appearances.

What do I have against experts? After all, we turn to them for our healthcare and legal advice. And you wouldn’t ask just anyone to check up on your car before a road trip. In fact, there are many forms of skill in our society, from practitioners of the trades, like plumbers and electricians, to people who help us with our taxes. But I contest that there is a difference between skill and “expertism,” and that difference has everything to do with celebrity. Your building contractor may have won accolades from the Chamber of Commerce, but it’s more likely that his success is attributable to his word-of-mouth reputation for quality on-time work than his online social media profile.

The other thing I have against our obsession with expertism, especially the celebratory sort, is the way it extends the caste system of capitalism. Here I am thinking less of the pro athletes with multi-million dollar contracts than about echelons of “professional” organizations, from architects to morticians, and including doctors, who control and extort wealth from society through their degree-based bona fides. If ever there was a racket, it’s the fortune to be had from membership in one of these modern-day “expert” guilds.

I will say, the area that feels most underrepresented by MasterClass is science and technology. While Jane Goodall and Neil deGrasse Tyson are well known personalities, it seems scientists are less likely to shill the scientific method than artists are with “creativity.” Or maybe scientists are just shy. Or more discreet.

As a lifetime member of “Expertise for Dummies,” where I don’t even have access to Cliff’s Notes insider advice, I will continue to practice plain old intellectual curiosity. If I ever reach such a low point that I feel the need to turn to celebrities for anything, maybe it will be to ask them how they became famous, or, more appositely, whether fame was all “that” once they finally lived up to it.

David Stairs is the founding editor of the Design-Altruism-Project.