David Stairs

Summer 2023 may be remembered as the year Americans finally awoke to climate change.

While choking smoke from Canadian wildfires enveloped cities like Minneapolis, Chicago, Detroit, and New York, places in the southwest suffered record high temps. Phoenix recorded twenty-seven straight days of 110° and nine consecutive nights of 94° or above. While people in the east were wondering why Canadians had to burn their forests, folks in Arizona might have been considering relocation. Aside from what we have heard for years about record droughts out west, the warming Pacific, exhibiting its periodic El Niño effect must be partially responsible. The other responsible party is none other than us.

Although wildfire is part and parcel of natural cycles, and many fires are caused by lightning strikes, these days too many wildfires are started by humans. Whether initiated by sparking or downed PGE wires, like the notorious 2018 Camp Fire that killed 85 people in Paradise, California, or the Eagle Creek Fire in the Columbia Gorge started the same year by a teen using fireworks, time and again the dodo birds come home to roost on human culpability. Not only are we responsible for pumping enormous amounts of CO2 into the atmo, but people start camp fires in high-risk areas, people explode fireworks at gender reveal parties, people take target practice in tinder-dry remote areas—— the word “people” is central to the catastrophe each time.

Unedited photo of the approaching Riverside Fire near Canby, Oregon, September 10, 2020. A smokey haze reflects the fire, resulting in this effect. Courtesy Lucien Stairs

The WUI or Wildland Urban Interface holds an ever-growing role in the burning of nature in the American West, and all parts of the world in fact. The Fort McMurray Fire of 2016 in the remote north of Canada’s Alberta Province resulted in the evacuation of 88,000 people, including 12,000 oil sands workers. Wildfires in 2022 and 2023 in Russia have resulted in millions of acres burned, with smoke traveling as far afield as the western US. Fires of such magnitude generate their own pyroclastic cumulus cloud formations and weather patterns, even generating lightning.

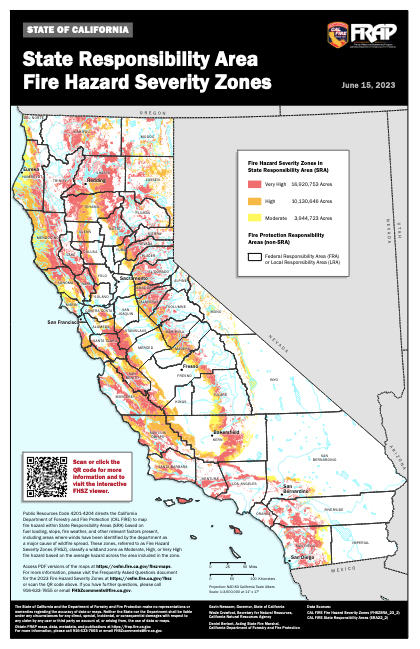

The WUI is especially problematic in regions with burgeoning populations. California, with just under 40 million inhabitants, heads the list. The state instituted a Wildland Hazards Building Code in 2007 and relies upon a series of Fire Hazard Severity Zone maps, updated in 2015, when evaluating building permits. The maps can affect choice of building materials and construction methods, as well as real estate disclosures at sale, and defensible space clearance requirements. Unfortunately, as with so many libertarian American systems, like healthcare, which is based upon personal risk management, this method does little to prevent the sprawl of the WUI. Haz maps are not a factor in insurance underwriting, which is modeled upon risk factors, and we know from experience that people will return to flood and fire zones to rebuild over and over again unless prevented.

California State Fire Hazard Severity Zone Map. Courtesy CA State Fire Marshall

Despite these limitations, California leads the charge in efforts to prevent and contain wildfires. The topic has even spawned a popular television series entitled Fire Country, based upon the operations of CalFire crews. Unfortunately, nature is unforgiving, and romanticizing the lives of brave men and women who put themselves at risk in the uneven battle between climate change and human stupidity has not stemmed the tide of wildfires. At least three people had died by mid-July 2023 while fighting fires in Canada.

Years of fire suppression combined with events like winter ’22-23’s record snowfall in the Sierras aid in the explosion of undergrowth fuel load. When this is followed by an early dry spring the potential for a long fire season is high. Needless to say, hyper-awareness for residents of the WUI will be necessary. This means behavior modification in any dryland areas by avoiding the many human activities that can trigger wildfire.

As the destruction mounts— more people died in Lahaina this summer than in the Camp Fire— people still seem to be in a state of denial. 20,000 evacuated from Yellowknife, Northwest Territory; Kelowna, B.C. threatened; the Bedrock Fire ravaging the Willamette National Forest sending choking smoke over Eugene; it’s difficult to believe that all it will take is an upsurge of in-home HEPA filter sales to assuage the pain. In a globe covered by smoke, wearing an oxygen mask becomes the default.

Francesca Mori-Kassell hiking through the remnants of the 2017 Rebel Fire in the Three Sisters Wilderness, Oregon. Courtesy Maya Mori

Of course, the more that burns, the more carbon is emitted into the atmosphere, creating a vicious feedback loop. If or until such time that it becomes necessary to regulate human settlement patterns in an effort to control wildfire, we will continue to see media accounts of worsening conditions, expanding fire zones, and increased insurance premiums, to say nothing of mortality stats. If 2023 does not inspire people in all parts of the northern hemisphere to petition their governments to negotiate and comply with climate change goals, then we are well and surely doomed.

David Stairs is the founding editor of the Design-Altruism-Project.