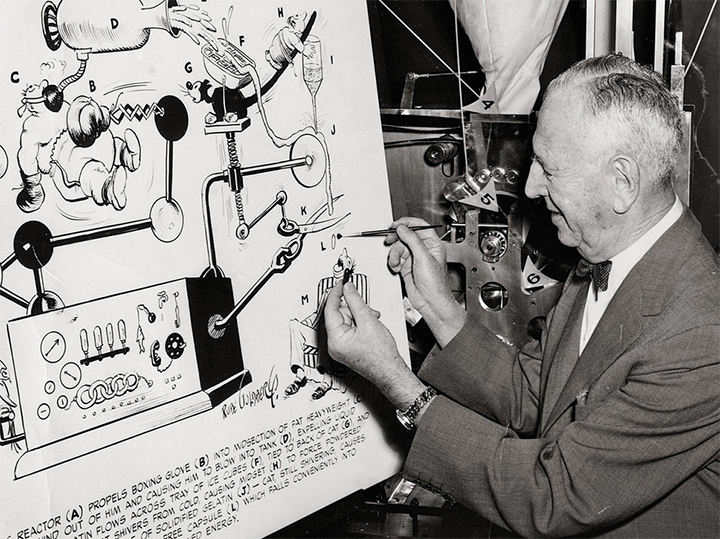

David Stairs

Rube Goldberg at work

© Heirs of Rube Goldberg

I’ve been hearing about the advantages of utilizing AI in design for about 5 years now. I attended a conference where the keynote was delivered by a woman who was working on a book about it. I do not remember being very impressed by her arguments, nor was she impressed with my criticisms.

Things certainly have changed. These days not a day goes by that I am not reminded of the benefits adhering to AI. Many periodicals run a regular column on the topic, conferences have special AI seminars, and my home institution “got into the action” with a symposium on the pros and cons of AI which I participated in. Not to mention that ChatGPT is on every student’s radar.

Needless to say, the social hysteria surrounding AI is reminiscent of the years leading up to Y2K. I hesitate to stretch the comparison further, primarily because there is so much more money involved. With Nvidia’s share price skyrocketing, and the influence of companies like OpenAI spreading like wildfire, I don’t think the obsession will end soon. And it is a social obsession.

When the social media of our exceedingly social species gets hold of a meme, everyone connected to our social technology feels compelled to “take a taste” or risk a huge and unrelenting case of FOMO. As it stands, everyone is experimenting with AI as if it is as important to the future as oxygen was to aerobic respiration two billion years ago. LLMs and LVMs are the stock-in-trade of AI programs, models that make unconsensual use of other people’s words and images to sell convenience to third parties.

Aside from the obvious opportunism of using this technology to speed-up investment decisions, or the nefarious political applications of “deep fakes,” AI strikes me less as the future of humanity than a covert kluge, or clumsy workaround for building mousetraps. While some people are using it to free themselves from business correspondence, others are busily developing new avenues into the Uncanny Valley. Machine knowledge, like machine language, combines the expensive and inefficient use of massive computing on gigantic server farms and applies it to discovering new ways to outperform individuals in small ways, as if Deep Blue and its dozens of engineers beating up Ken Jennings on Jeopardy were a noteworthy accomplishment.

The late philosopher of technology, Daniel Dennett, wrote compellingly in last May’s Atlantic about the need to criminalize efforts to create “counterfeit people.” The gist of his argument was that civilization is so fragile that it will not be able to withstand the damage caused when AI personalities destroy trust. Therefore, he concludes, examples should be flagged and perpetrators, whether corporate or criminal, should be fined or imprisoned.

So long as computer science considers a mechanical representation of sentience as the highest good, it will remain locked in a Frankensteinian death embrace with world capital. This is fundamentally different from the “computer revolution,” which was individualized, and unlike the advent of the Internet, which was about collective communication. Although those technologies took time to show a return on investment—— decades in the case of computers, the current rush to make a killing on AI is less like a gestalt shift than a gold rush.

It’s possible that my skepticism is misplaced; I have been wrong before, and have had to reverse my position. Many times. But technological obsession is such an insipid fascination, too readily adopted and too easily excused, that I feel more uneasy jumping on the bandwagon than possibly being wrong about the future of AI.

The American cartoonist Rube Goldberg, a Master of complicated useless machines, became their namesake. But he was not the only one. Creative people the world over have designed such humorous “contraptions.” I can only imagine many would’ve been insulted at the suggestion that their imaginations would soon be replaced by Open AI’s CLIP. Here’s to kluges that are overtly “klugey.” The rest may be fake, but they certainly are not deep.

David Stairs is the founding editor of the Design-Altruism-Project.